This weekend marks the centenary of Bloody Sunday and, in this second part of his article, Tom Lyons recounts the events of that fateful day in 1920 ...

THE first quarter of 1920 saw the GAA trying to carry on its activities as if normal life was continuing. At a quiet Congress, plans were revealed for the development of Croke Park and it was decided that all future All-Ireland finals would be played there. Little did any delegate realise that, within the year, the sod of Croke Park was to become hallowed ground.

From March onwards there were definite signs of a fall-off of activity on the playing pitches as the country sank into a state of war. Harassment of GAA clubs and personnel was especially intense in Munster and, in July, the Munster hurling semi-final had to be moved out of the Cork Athletic Grounds because of interference from the military.

A prohibition on all public meetings almost brought an end to the playing of games and then the county board decided to halt all activity in sympathy with the now-dying Terence McSwiney. By December, all Munster, bar Waterford, was under military rule and the games were at a standstill.

In October an attempt was made by the national executive to revive inter-county activity, which was to have such a tragic consequence a month later. Tipperary was one of the foremost football counties at the time and when Dublin questioned their superiority, the Tipp county board issued a football challenge to Dublin and a match was arranged for Sunday, November 21st, at 2.45pm. Receipts would go to an injured player and the Prisoners’ Fund. Nothing was to more closely illustrate the connections between the GAA and the republican movement than the events of that tragic day, Bloody Sunday.

The sports ground in Jones’s Road in Dublin, where Dohenys played their All-Ireland final of 1897, had been bought by the GAA from former GAA president, and strong IRB man, Frank Dineen, in 1913 and, in 1919, a record crowd of 32,000 had watched Kildare beating Galway in the All-Ireland final.

Following that final, it was decided to carry out major improvements to increase the capacity and the plans included the complete relaying of the sod. This work saw the grounds closed for most of the spring of 1920. It was on this new sod that the blood of innocents was shed in November.

As the crowd was gathering for the Tipperary v Dublin game on November 21st, word was spreading of a major IRA activity in Dublin that morning. On the directions of Michael Collins, with the authorisation of the Dáil Cabinet, the republican counter-espionage service had executed fourteen British intelligence officers in their lodgings in the centre of Dublin, whose mission had been the identification and assassination of Sinn Féin leaders. Collins had got his blow in first, thus destroying the centre of the whole British spy network in Ireland.

On hearing the news, Nolan and O’Toole had considered cancelling the match, realising that retaliation of some sort was inevitable by the British forces, but decided to proceed. By coincidence, the previous day, the Dáil Cabinet had debated a request from the GAA for a loan of £6,000 as the association was in serious financial difficulties owing to the political situation and the cessation of activity.

The Dáil eventually approved the loan, no doubt influenced by the events of Bloody Sunday, and the association was saved from bankruptcy.

A crowd of over 10,000 had gathered in Croke Park for the game when, at 3 p.m., a British military aeroplane flew over the grounds and emitted a red flare. Almost immediately Black and Tans began to climb over the walls at both ends. At once, gunfire was directed into the unsuspecting crowd, first from small arms and then from a machine gun, set up at the entrance.

After about ten minutes an RIC officer walked across the pitch, announcing a search of the crowd. A stampede resulted and little can we imagine now the horror and terror of those minutes as the crowd tried to escape the deadly gunfire.

Most of the crowd was detained and it took some hours to conduct a full search, but 14 people lay mortally on the ground, with over 100 injured. Most died then and there, while some died from their wounds in hospitals during the following week.

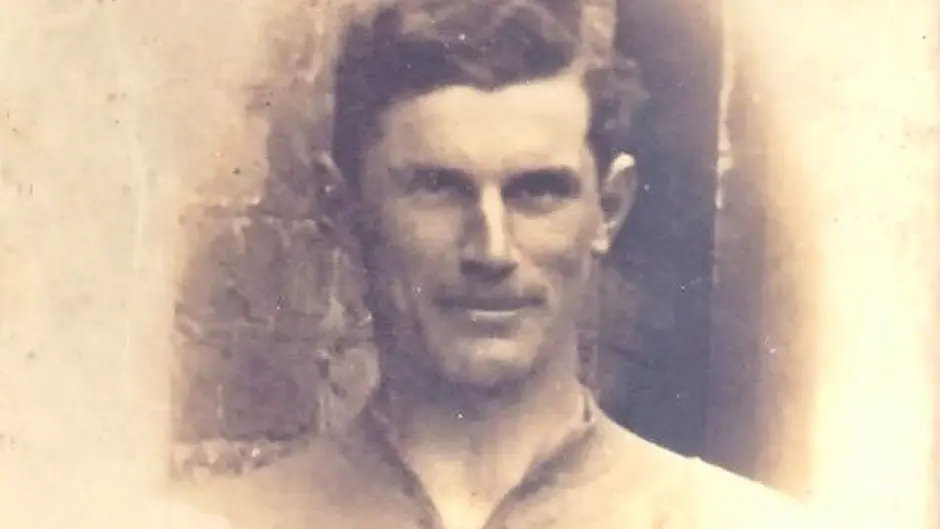

Included among the dead were the Tipperary captain, Michael Hogan; a young Wexford man who tried to assist him; a 26-year-old Dublin woman due to be married a few days later; and three Dublin boys aged 10, 11 and 14. Hogan, a native of Grangemockler, was only 24 years of age and a member of the IRA.

On the train journey to Dublin that Saturday, he and his team-mates had been involved in a fight with soldiers of the Lincolnshire Regiment and had thrown them off the train. That night he didn’t stay in the official team hotel, Barry’s, for fear of reprisal.

It is said that he was advised by Dan Breen not to attend the match but to return to Tipperary as quickly as possible. He was shot in the back as he attempted to crawl towards the safety of the side hoarding.

It is worth noting, too, that, on Bloody Sunday, Tipperary were to wear the blue and white jerseys of county champions, Fethard, but as those jerseys were not in good condition, they wore the white and green of Grangemockler instead.

One of the people in Croke Park that day was a young man named Frank Doran, a Kildare native. He migrated to Clonakilty a few years later and worked in Darrara Agricultural College all his life. He was a renowned GAA historian, activist and poet and often told the story of how he fled from the grounds and hid in a hen house in a nearby garden until the military departed the scene.

As the last of the military lorries left, they dragged the Tri-colour flag that always flew over the grounds along the ground behind the lorry. From start to finish the raid was planned as a vicious reprisal for the British deaths that morning.

At home and abroad, the official explanation of the British military, that Michael Collins’s men were hiding in the crowd and had fired first, was roundly rejected and no public official enquiry was ever held.

Unlike 1916, when the GAA had been accused of participation and had officially rejected the accusation, there was absolutely no contact between the Association and Dublin castle, no protest to the British about the raid. The GAA had been singled out for revenge by an indisciplined military, some of whom were actually drunk at the time, and this again emphasised the part that GAA people were playing in the fight for freedom. The GAA was quietly proud of that position.

When a new stand was built in Croke Park in 1924, it was called the Hogan Stand. Even though the new super stadium that is Croke Park now is a far cry from the original Croke Park and the newly-laid sod of 1920 is long, long gone, the spirit of the 13 innocent people who died there on November 21st, 1920, will always remain to remind people of a time and an age that gave us, at a very high price, the freedom we now enjoy to be who we are and what we are.

Bloody Sunday will always be part of the GAA.