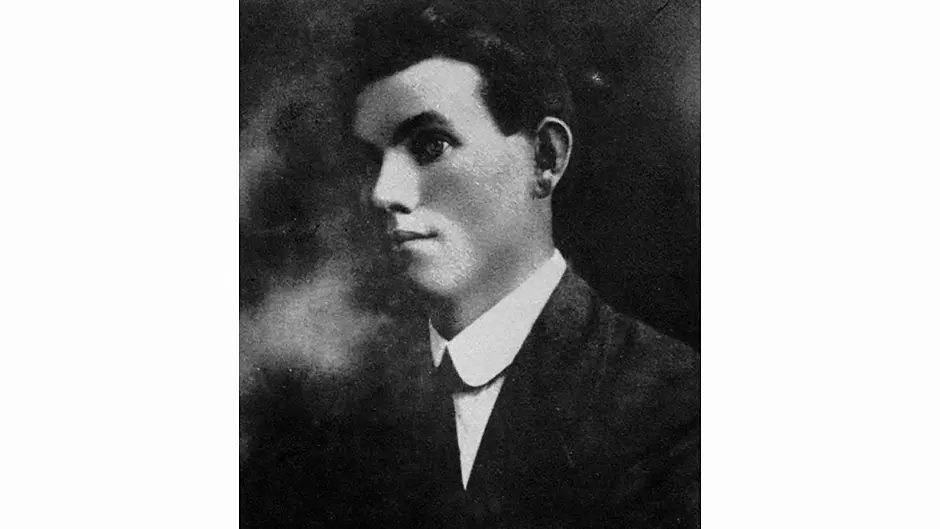

As the centenary of Richard (Dick) Barrett’s execution takes place this week, historian Alan McCarthy looks back on the life of the patriotic Ballineen man

EXECUTED on the Feast of the Immaculate Conception in Mountjoy Gaol on December 8th 1922, Richard (Dick) Barrett was born on December 17th 1889 and raised in Hollyhill, Ballineen.

Tom Hales described the Barrett family as small farmers who saved money to educate Richard in the hope that he would ‘be able to help them some day.’ He was duly educated at Knocks and Knockskeagh national schools, and the De La Salle College in Waterford.

Having qualified as a teacher, he took up a position at the Upton industrial school in early 1914 and subsequently became principal of Gurranes national school.

He was a committed Irish language enthusiast and, as well as being a talented footballer in his own right, was honorary secretary of Knockavilla GAA club (later part of Valley Rovers) with the Cork County U21A Hurling Championship trophy bearing his name today.

Richard Barrett joined the Irish Volunteers/IRA in 1915 and served during the War of Independence, truce period and Civil War. He succeeded Pat Harte, who had been captured and brutalised by the Essex Regiment, as Brigade Quartermaster in 1920.

Barrett later served as assistant divisional quartermaster and assistant quartermaster general of the anti-Treaty IRA at the commencement of the Civil War. He was part of the Four Courts garrison and was captured after its surrender on June 30th 1922.

Barrett’s internment in Mountjoy which ended with his execution was not his only experience of incarceration during the revolutionary period. During the War of Independence he had been imprisoned in Spike Island, ultimately escaping in a daring bid for freedom alongside Tom Crofts, Bill Quirke and others. Annie Farrington, proprietor of two Dublin hotels frequented by the IRA recalled in her Bureau of Military History witness statement that Barrett ‘was a very nice boy too and had a good sense of humour. He was a delicate sort of lad … They were lovely people to have in the house, they were so well-behaved.’

During the War of Independence, Barrett had travelled to Dublin to visit IRA GHQ alongside Tom Hales. The Hales brothers infamously split over the Treaty. Seán, a pro-Treatyite TD, was assassinated during the Civil War, leading to the reprisal execution of Barrett and others without any legal process.

In his farewell letter to his family, the blending of Barrett’s idealism and stoicism in the face of his execution alongside his reflection on intimate family ties is quite striking.

He wrote: ‘Remember it is sweet and glorious to die for one’s country. There were three others brought out with me, Liam Mellows, Rory O’Connor and Joe McKelvey, I presume that these three great men will also pay the full penalty for loving Ireland … I was not as good a son or as loving a brother as I might have been/I have caused you all a lot of worry and uneasiness but I know you will forgive me.’

Barrett and his comrades’ bodies were buried in the prison yard but were reinterred in 1924. Commenting on the funeral procession in 1924, a contributor to the Irish Folklore Commission noted that ‘the remains were borne on the shoulders of his comrades from Enniskeane to Ahiohill churchyard, a distance of six miles, in torrential rain … The funeral cortege was so large that it would almost seem that all Republican Ireland had assembled to honour the dead patriot.’

There is some anecdotal evidence concerning what may have been Barrett’s last words or that he sang while heading out to face the firing squad. Another aspect of the folklore surrounding the executions is that each victim was supposed to represent a province of Ireland. This is, however, problematic. Liam Mellows fought in Galway in 1916 and is commemorated there but wasn’t from Connacht. More than likely, these men were selected because they were four high profile leaders within the anti-Treaty IRA, all being members of the army executive.

Mellows’ biographer CD Greaves disputes the idea that he represented Connacht, noting soberly that all four were prominent anti-Treatyites and all had at some point been members of the IRB. but left. In his last letter to his mother, Mellows specifically requested to be buried with his grandparents in Castletown, Co Wexford. The idea that the men represented a province seems to be a poetic creation of republicans who came later.

Barrett and his comrades were four of the six total official executions in Dublin during the Civil War. While their deaths may have been interpretated as representative, only a handful of leaders were executed during the conflict.

Instead, government policy targeted the rank and file to demoralise the IRA and conducted executions nationwide to illustrate government control of central and peripheral locations, rather than targeting representative figures in the capital.

Ernest Blythe said in the Dáil: ‘There was, of course, no discussion of names by the Cabinet. The names presumably were selected by army officers as those of men whose execution would be most calculated to have the maximum warning effect on members of the irregular forces in all parts of the country.’ While all four were well-known figures, there is no concrete evidence that provincial consideration was a factor.

In 1934 the Army Pensions Board awarded a partial dependents’ gratuity of £112.10.00 to Barrett’s mother Ellen in compensation for his killing. Her application had been supported by references from both Tom Barry and, fittingly, Tom Hales. The Southern Star wrote at the time under an editorial entitled ‘Assassination and Reprisal’ that ‘Horror crowds out horror and tragedy galls the heel of tragedy in this stricken land.’

• Alan McCarthy is a historian of modern Ireland. He is the author of ‘Newspapers and Journalism in Cork’, 1910-23 (Four Courts Press) and the forthcoming history of adult education and lifelong learning at UCC, 1946-2021.