As threats to our energy supplies are mooted this year, Robert Hume looks back at the introduction of electric light in West Cork, 100 years ago this very week

IN October 1921, the ‘no small venture’ of lighting Skibbereen with a ‘new illuminant’ was close to completion.

The first electric street lamp in Ireland had been installed outside the Freeman’s Journal (forerunner to the Irish Independent) offices at Prince’s Street in Dublin in 1880. By the early 1920s, 130 Irish towns – including Bandon, Bantry, Clonakilty and Dunmanway – were receiving public electricity.

The funds needed by the Skibbereen Gas and Electric Light Company were secured mainly from local people. Five-pound shares were issued, and investors paid a ‘handsome’ 7% gross dividend.

By October 1921, the lamps in Skibbereen’s Main Street were fully operational, each emitting 200 candlepower. Those in outlying streets gave off 60 candlepower. Altogether there were 44 public lights, which cost ratepayers a total of £186 per year. They stayed on until 11.10pm, when they were extinguished on military orders.

In 1926, the Town Hall clock no longer had to envy Big Ben, because it got its light too!

‘No more shall we hear complaints that, by the time the lamp-lighter had lit up the last gas lamp, it was nearly time for him to commence extinguishing,’ applauded the Skibbereen Eagle (October 15th, 1921).

Besides, gas supplies had recently been poor. No coal had arrived at Baltimore due to the miners’ strike, and the gas had been shut off every night from 7pm until 8.30am in May.

Now, by shifting a switch at the Works, all the lamps came on together. ‘From the top of Cork Road to the extremity of Upper Bridge Street, all the way is aglow simultaneously,’ continued the Eagle.

The new electric lamps were able to ‘dissipate the darkness’ over a greater area than gas, because they were placed on taller posts.

They also emitted a more uniform glow. When the gas supply was low it would be noticeable in every lamp: gas caused ‘as much malediction as the tax gatherer’. To read in comfort at home was impossible, and ‘everybody got irritable’.

Electricity allowed churches and public halls to be completely illuminated, whereas before ‘huge spaces of gloom should always remain in shadow’.

By November 11th 1922 The Southern Star was reporting that even in the town’s side streets full power had been achieved.

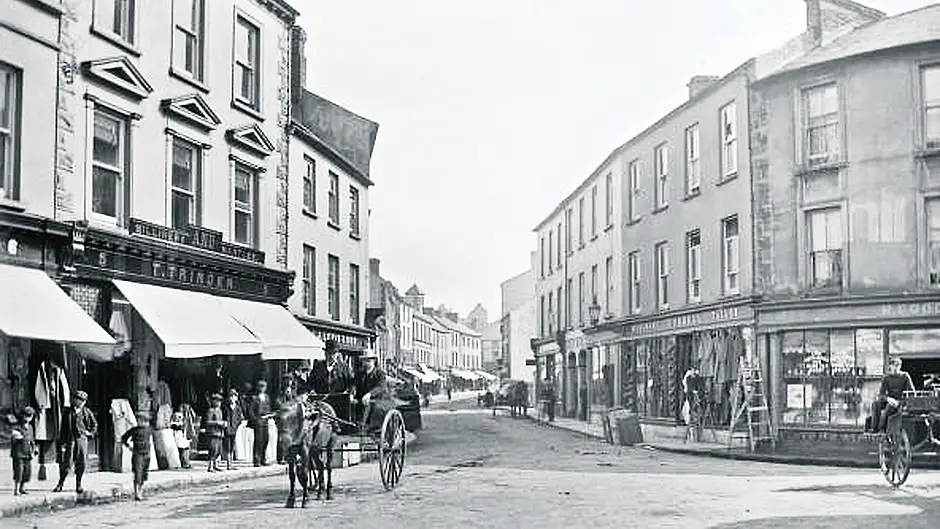

Gas lighting existed in Skibbereen since August 1868, when 40 street lamps, fuelled from the gasworks (today’s Skibbereen Heritage Centre), were lit for the first time. ‘The effect was magical and the change from darkness into light was warmly welcomed by an intense and admiring multitude’, reported the Eagle. Why replace them when, for so long, they had ‘safely guided our steps?’

One inhabitant complained: ‘Wasn’t North Street or Main Street just as bright before?’ Mr O’Driscoll went further: ‘the old gas light was better than the present electric light’ (The Southern Star, October 8th 1921).

Some people perhaps preferred the orangey glow of gas to the harsher, white glare the electric ‘arc’ light produced.

Critics worried that public electric lighting was the thin end of the wedge: electricity would not only replace gas in the lighting of homes, but in cooking it would make gas ovens and rings obsolete.

Like gas, electricity was also produced from coal, which continued to face supply problems, and now there was an added danger: electric shock.

When the project was initially proposed, the Skibbereen Eagle (March 6th 1920) referred to ‘the universal suspicion with which sellers of anything and everything are at present regarded’.

Electricity charges, as predicted, proved expensive.

On November 28th 1925, ‘Mr D McCarthy’ wrote to The Southern Star acknowledging that the Skibbereen Electric Lighting Company was reducing its prices for lighting the streets, but not by a ‘very generous’ amount, and that its ‘soft customers’ were still being ‘fleeced’.

Inhabitants were paying two and a quarter times those in Dunmanway, he noted.

A serious criticism regarded the insufficient number of lamps installed. In south Main Street a long stretch was in darkness, and between the bridge and the Young Men’s Society door, there was no lamp at all.

No evidence is recorded about what criminals thought of the dearth of shadows and gloomy spaces in the more brightly-lit streets.

But fewer murders and robberies seem to have made the pages of the two West Cork newspapers after the new illuminant made its controversial appearance.