An estimated 20,000 people have been diagnosed in Ireland with haemochromatosis – the disorder which can lead to dangerously high levels of iron in the blood – and it’s estimated that one in five people could carry the gene. Southern Star editor SIOBHÁN CRONIN is one of those 20,000

HAEMOCHROMATOSIS… can I explain it? I can’t even spell it!

It sounds a bit like the rabbit disease of myxomatosis, but you’ve made a ‘hames’ of pronouncing it from the start.

But we better get used to pronouncing it in Ireland, because very soon everyone is going to know a lot about it.

Haemochromatosis (or ‘iron overload’) is an inherited disorder which causes the body to absorb too much iron. If left unchecked, excess iron gradually accumulates in organs like the liver, pancreas, joints, heart or endocrine glands. And, of course, that then leads to its own – often serious – problems.

The research into the disorder is relatively recent, with the gene only isolated by scientists in 1996. This is why so many older people lived their lives undiagnosed, but often suffered from the effects.

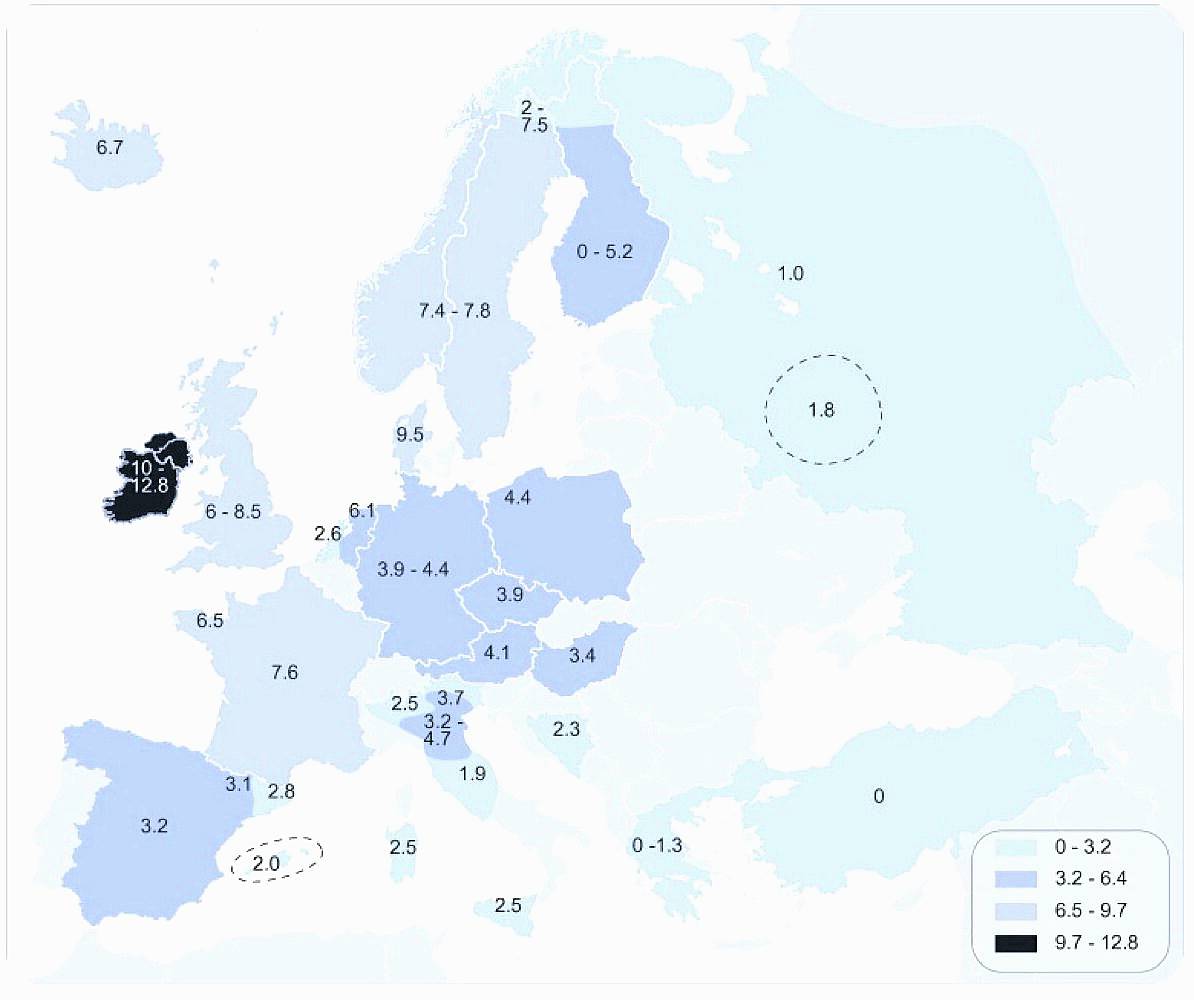

It’s estimated that one in five Irish people are carriers of the gene – and about one in every 83 people are at risk of developing haemochromatosis. Ireland has the highest rates of haemochromatosis in the world, leading it to be known as the ‘Celtic disease’.

It’s about three years since the first of my four sisters was diagnosed with it – and since then the rest of us have been – sometimes reluctantly – tested, and we all have the gene.

At the haemochromotosis information meeting in Cork were, from left: Frank McHugh, IHA; Miriam Forde, IHA; Prof Diarmaid Houlihan of the Bons, and Cllr Damian Boylan.

At the haemochromotosis information meeting in Cork were, from left: Frank McHugh, IHA; Miriam Forde, IHA; Prof Diarmaid Houlihan of the Bons, and Cllr Damian Boylan.

That first sister’s diagnosis was the result of a very thorough GP suggesting the test, while the next in line admitted that a high iron count in her early 40s was dismissed by her GP as not being worthy of any further probing.

Doctors differ, as they say, and Blarney Cllr Damien Boylan had a similar story about his own father, as he told a recent information meeting in Cork, organised by the Irish Haemochromatosis Association (IHA).

Cllr Boylan said his father was diagnosed many years ago with liver cirrhosis and his GP gave him a very stern dressing down about ‘lying’ about drinking. Damian said his father was perplexed because he certainly wasn’t a drinker. But, of course, they later learned that he had, in fact, haemochromotasis – and an ignored iron overload can lead to cirrhosis of the liver, even if you never took an alcoholic drink in your life.

For me, the diagnosis came as a shock on so many fronts.

With so many affected in my family, we can only surmise now that both of our deceased parents carried the gene – and were, more than likely, affected by it too.

Both my parents suffered heart issues – my father died of a massive heart attack at the age of 65 and my mother had triple bypass surgery at just 70. She also suffered with arthritis which can be another giveaway.

We now all wonder if they had been diagnosed, would their health outcomes have been more positive.

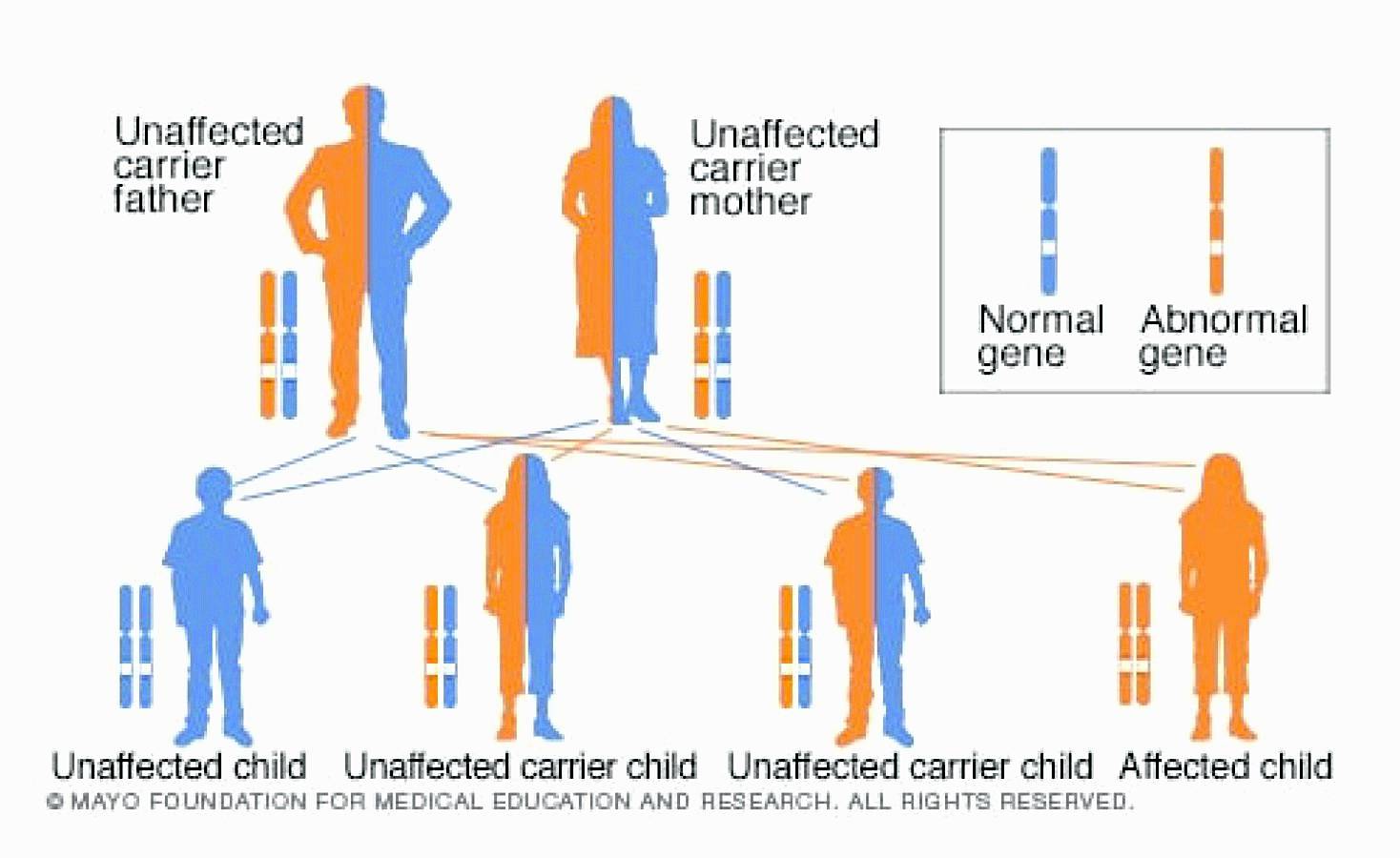

The graphic explains how some people develop haemochromotosis while others are simply carriers of the gene.

The graphic explains how some people develop haemochromotosis while others are simply carriers of the gene.

Added to that, is the knowledge that the remedy for high iron is to give approximately a pint of blood regularly. My sister whose high iron levels were spotted 20 years ago, but never treated, found herself giving blood every fortnight for a year, because her iron was so high by the time she was finally diagnosed. This treatment is called ‘venesection’.

Now, as someone with a lifelong phobia about blood, needles and the word ‘vein’, the idea of giving blood is at the top of my list of ‘must-avoid’ experiences.

On the few occasions that I have had to get my blood tested in my life, I have suffered major internalised trauma. I am always putting on a ‘brave’ face, but inside I am in apocalyptic turmoil – at least that is how it feels from in here.

Even typing the word ‘vein’ now makes the… em… blood… drain from my fingers. And, coupled with all this, is the fact that my veins (uggghh) are hard to find so I have rarely been able to be tested without a huge amount of drama involving several nurses, a tourniquet moving from arm to arm, and a lot of thumping and squeezing and shouting – and that’s just from me.

I usually have to take a long lie down afterwards, and am marked with several black bruises (oh, did I mention I bruise easily?) for several weeks. And all for a teeny tiny amount of blood.

‘You don’t really want to give up your blood easily, do you?’ the nurse asked me recently when I was having my latest ferritin (the blood protein that contains iron) test.

It made me wonder why I have been so fascinated with vampires my whole life – there must be something in that for the psychology lab, for sure, if not the blood lab.

Ireland has more cases of haemochromatosis than anywhere else in the world, and it is often dubbed the ‘Celtic disease’.

Ireland has more cases of haemochromatosis than anywhere else in the world, and it is often dubbed the ‘Celtic disease’.

And to put the final tin (iron) hat on it all, my two favourite drinks – Guinness and red wine – are firmly on the ‘naughty’ step when it comes to adjusting your diet for haemochromatosis.

As well as regulating your blood levels, keeping an eye on what you eat can certainly help, as Prof Professor Diarmaid Houlihan told us at the IHA information meeting in Cork.

Prof Houlihan is a consultant gastroenterologist at the Bons Secours in Cork and he has been studying the disorder for many years.

During his brilliant talk on the pros and cons of the disorder he said he believes that liver disease is the ‘poor relation’ in Ireland when compared with the emphasis put on heart disease.

But at least Prof Houlihan also has a great sense of humour – he put an image of a vampire bat on the screen when it came to the slide about ‘goals’!

‘My mission is that nobody goes undiagnosed,’ he said, adding that he has been calling for a national screening programme for the disease – a goal shared by Cllr Boylan, who, eerily, described it as the ‘silent killer’.

Prof Houlihan said the genetic test has only been available in his lifetime, and he was aware of many people who were told in the past to cut back on alcohol because of liver issues. Yet, even when they did that, unbeknownst to them, their high iron levels continued to damage their organs.

My first ferretin test, about a year ago, came back with normal levels – possibly due to my vegetarian diet. But I am currently awaiting the latest result, as very often the levels rise as you get older. Thanks to my diagnosis, I can keep an eye on it now.

But Prof Houlihan says we need to start testing people in their 30s and 40s, though he admitted that it was only on entering menopause that many women are picked up as sufferers, as menstruation often masks the issue.

Describing liver cancer as an ‘epidemic’, he said rates had risen 300% in the past two decades. In the light of other diseases, ‘the liver has been forgotten about’, he said, and we need to start taking it more seriously.

It was suggested at the meeting that local sports clubs, like the GAA, should start alerting young people to the dangers of haemochromatosis, in the absence of a national awareness campaign.

Audience members also commented that that rise in the diagnosis of the disorder, combined with a shortage in blood-donors, might lead to some joined-up thinking by the Irish Blood Transfusion Service. The blood taken during venesection is perfectly good blood, there is simply too much of it.

We might just have to cut out that once-recommended post-donation glass of Guinness, though!

• For more see IHA.ie