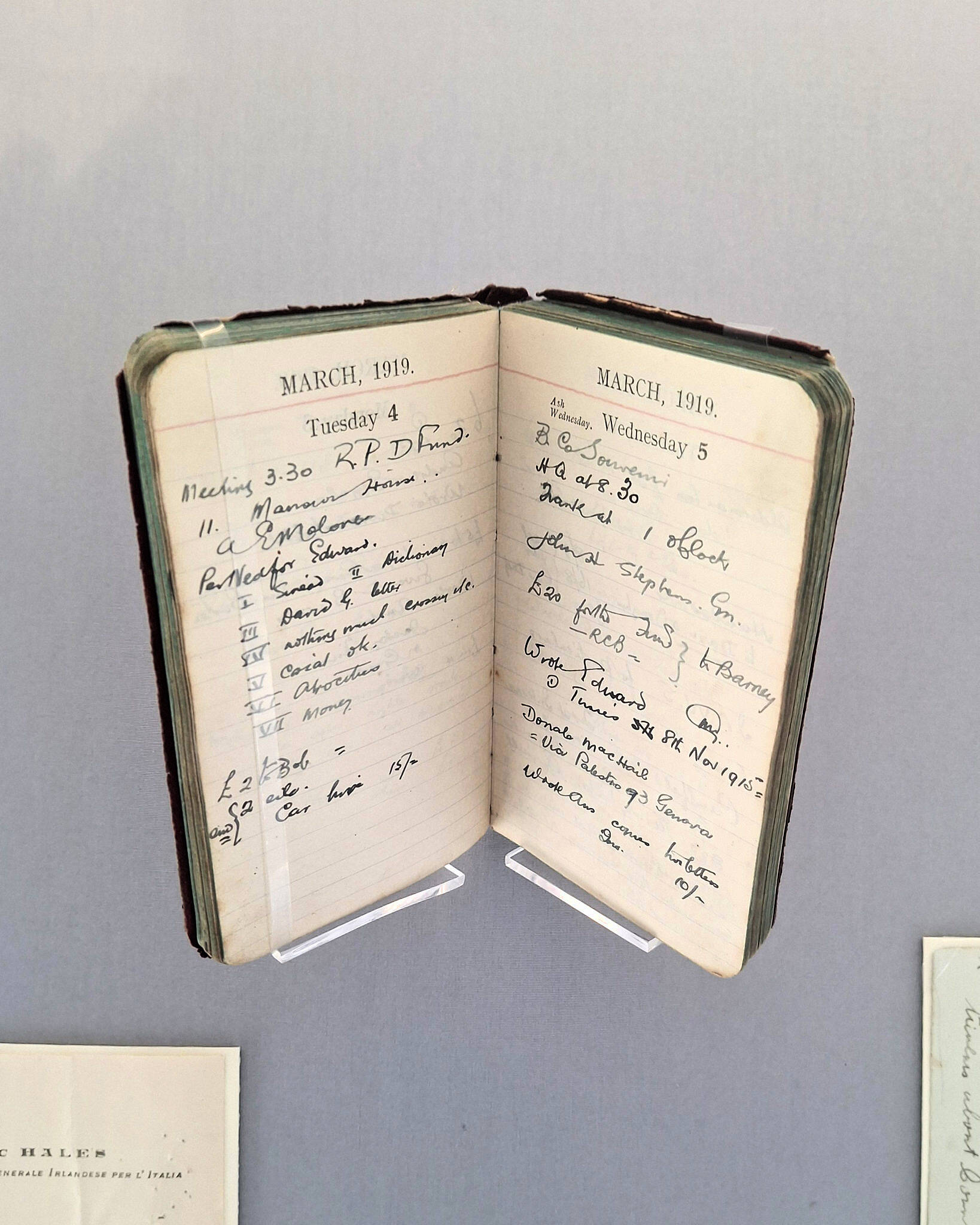

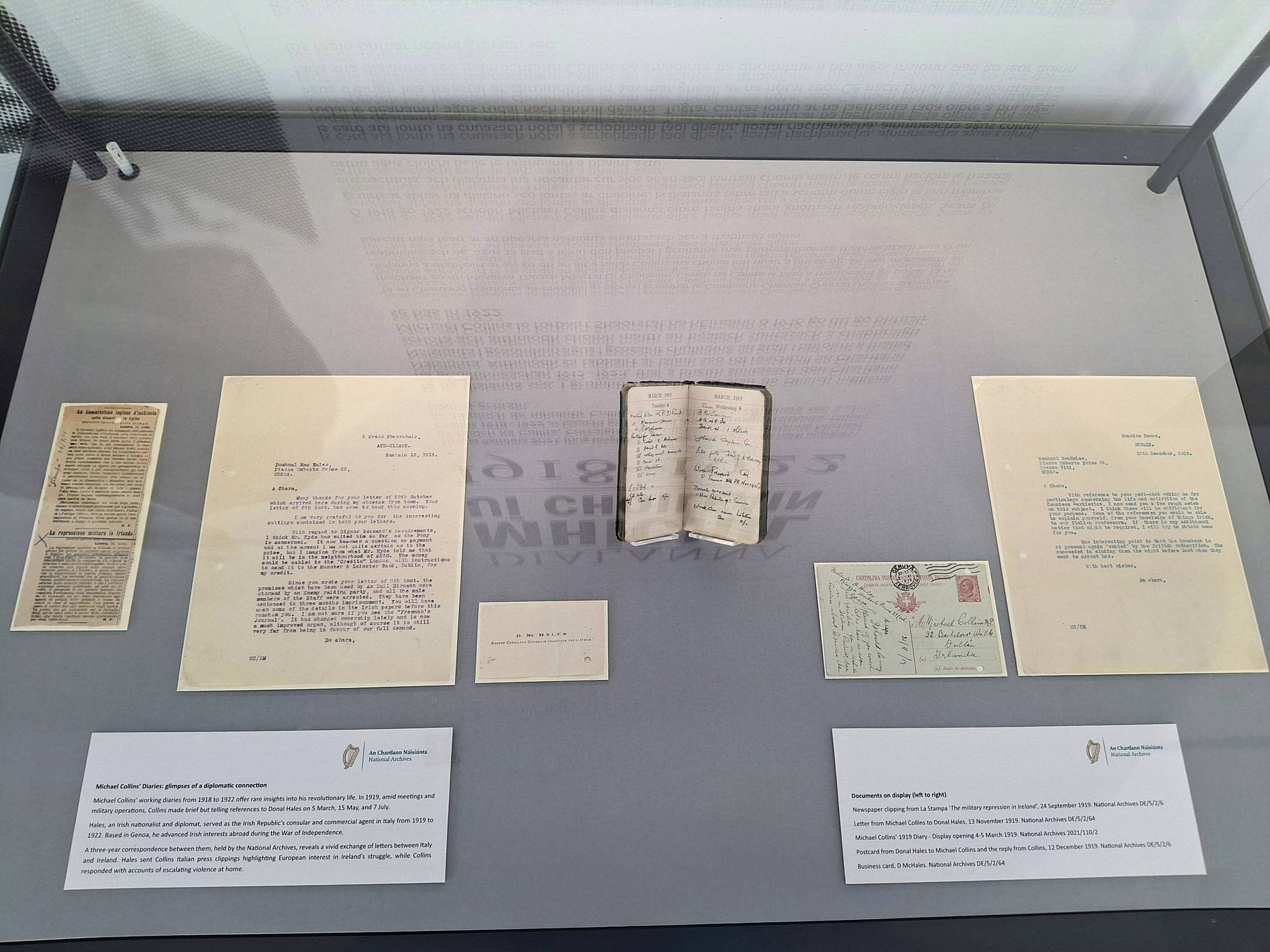

The Michael Collins Diaries 1918 -1922 return for their annual residency at Clonakilty’s Michael Collins House Museum. In partnership with Cork County Council, the National Archives loan the diaries to the museum every August and this year’s exhibition will have a continental feel.

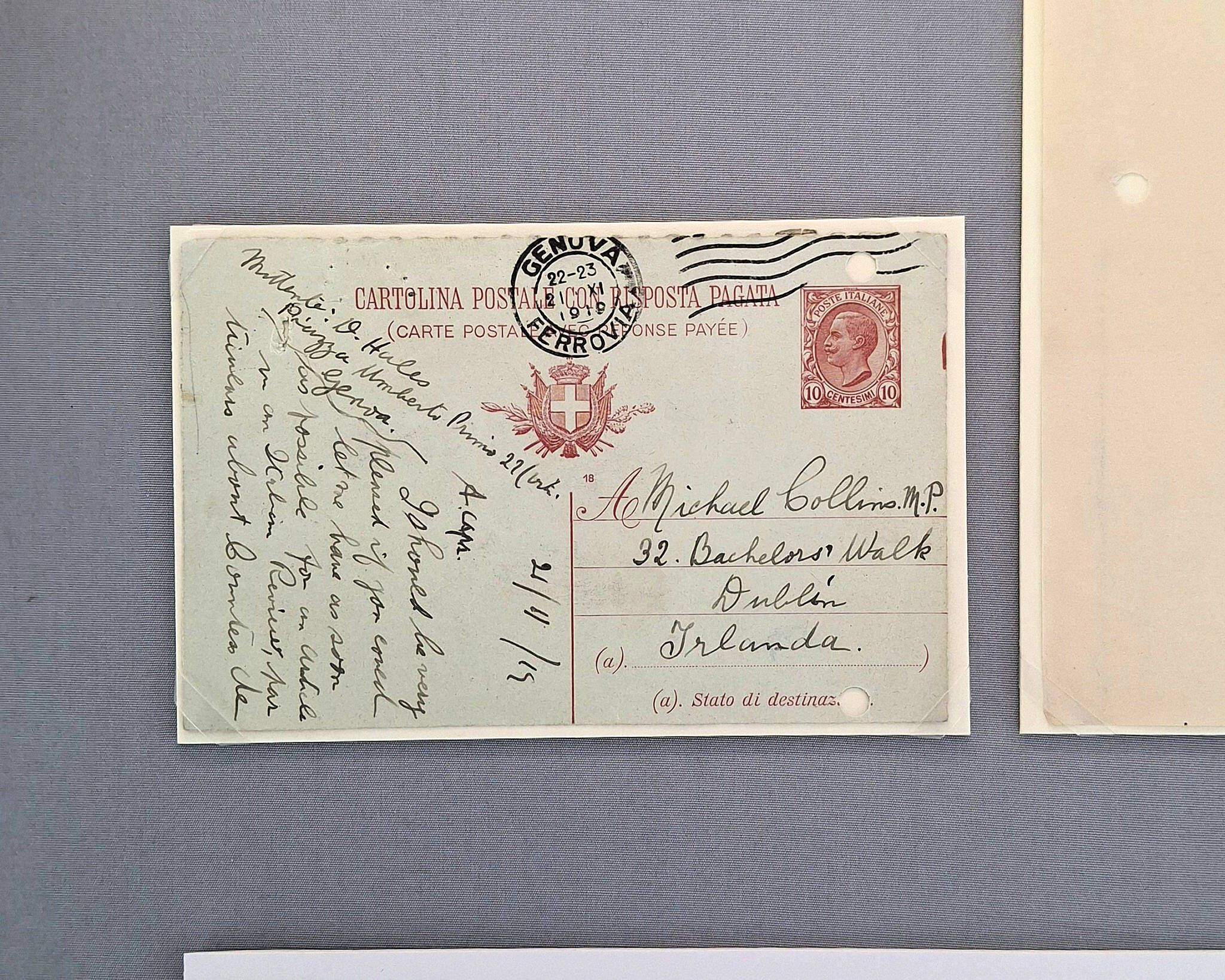

For the first time a selection of letters exchanged between Michael Collins and an Irish diplomat based in Italy between 1919 - 1922 will go on public display.

The Irish diplomat was West Cork man Donal Hales.

Acting as the Irish Republic’s consular in Italy, Donal Hales sent regular letters along with clippings from Italian newspapers to Michael Collins.

Hales went to work in Italy as a teacher shortly before the outbreak of World War I.

The West Cork native taught languages at public and private schools. He married an Italian lady and settled in Genoa but, never forgot his homeland.

Hales was vocal on the Irish fight for self-determination and wrote many articles for Italian newspapers about the political situation in Ireland.

In 1919 at the behest of Michael Collins, the Dail Eireann minister for trade Ernest Blythe appointed Donal Hales as consular and commercial agent in Italy for the Irish Republic.

Hales became an important mouthpiece in Italy for the Irish republican movement.

He received weekly updates from Collins and Hales would then inform the Italian press about the weekly occurrences in Irelands fight for freedom.

In the letters sent between Hales and the ‘Big Fella’ you see a mixture of work and the personal. Light hearted mentions of weather mixed with the hard realities of guerilla warfare.

Apart from diplomatic and propaganda work, Hales was also a key contact in Europe for the procurement of arms. He was the key driving force behind a plan to arrange a big purchase of rifles from the Italian military in 1921 and have them shipped, with the aid of the Cork IRA, to landing points along the west Cork coastline.

Michael Leahy, a marine engineer and officer of the Cork IRA No.1 Brigade, was tasked with helping bring the arms from Italy to Ireland.

He travelled to Genoa to meet Hales and organise the shipment of arms. In his Bureau of Military History witness statement in 1951 Leahy recalled his first impression of Donal Hales as being ‘more Italian than Irish.’

Money for the weapons was raised by Collins and sent to Italy but, the transaction never happened and the plan was abandoned due to the high risks involved.

Leahy returned home disappointed and Hales was left disgruntled with the outcome of what Leahy stated was his plan to arm the Cork IRA.

Donal Hales came from a staunch nationalist family in Knocknacurra, Ballinadee. His brothers Sean, Bob and Tom all took up arms and fought for the IRA in the War of Independence.

Unfortunately when the civil war broke out, like many families across Ireland the Hales siblings found themselves on opposing sides of the bitter conflict.

Sean, who became a Pro-Treaty TD was shot dead in Dublin. Tom fought with the Anti-Treaty IRA while Donal in Genoa also took the anti-treaty side and for this he lost his diplomatic position in Italy.

Years after the end of the civil war, Donal, who continued to live in Italy, commissioned a statue of his brother Sean who was shot dead by the anti-treaty IRA in 1922.

Despite taking the opposing political side during the civil war, Donal made sure that his brother was commemorated in West Cork with a marble memorial from Genoa. It was unveiled in Bandon in 1930 at what is now known as Sean Hales Place.

The often overlooked international aspect of the War of Independence can now be seen through the Donal Hales correspondence.

The fascinating letters, and the Michael Collins diaries, can be explored through an interactive touchscreen display at the Michael Collins House Museum throughout August, with admission to the diaries exhibition free of charge.

– Pauline Murphy, historian