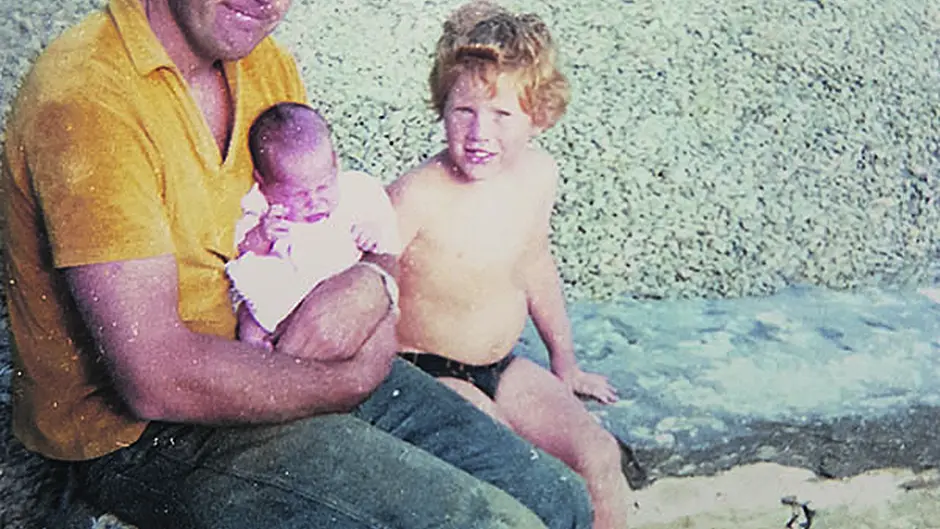

Michael Kingston was celebrating his 4th birthday when his father left his Goleen home for the nighshift on Whiddy. Michael would never see him again. That night changed Michael forever

IT was my 4th birthday celebration on Sunday 7th January 1979 as my father, Tim, left my home in Goleen to drive to Bantry.

It was the last time that I would see him.

He boarded the offshore jetty at 8pm as an oil pollution control officer for the nightshift, having stepped in for his colleague who wanted to take his wife shopping in the sales in Cork.

Being the kind man, and I should say, very young man (31) that my father was, with his whole life ahead of him, he willingly obliged his colleague.

But a few hours later, about half past midnight, everything changed. A fire, spreading from, or beside, the oil tanker Betelgeuse, started to engulf the jetty.

My father spent 20 minutes trying to radio for help, but those that could and should have turned on the fire hydrants and send out the safety boats were absent.

In those 20 minutes my father – a strong swimmer who had dived only a few days earlier checking the pylons of the jetty – could easily have saved his own life and swam, with others, to safety.

When it was too late, when human error had played its part, and intervened and prevented nature’s natural ability to save itself, my father and others took to the water.

My father had effectively remained at his post in the most atrocious circumstances until the last.

For eight months my father’s body lay at the shore of Whiddy Island until mercifully the sea gave it up, along with Cornelius O’Shea and, in the same place, shortly after, Denis O’Leary, after the Fastnet storm of that summer.

Mrs O’Leary always believed that my father must have tried to save her husband as they were found together and he could not swim.

I could not bring myself to read the Whiddy Island Tribunal Report until nearly 20 years later.

I was afraid of it: it held dark secrets, I thought, in my mind. The first time I started to look at it in the library in UCD in November 1996, that night I received news that my beloved uncle with Down syndrome, my father’s brother, had died. I put it away.

But the report doesn’t hold those secrets, of course. It is what is not in the report.

The ‘Suppression of the Truth’ and the subsequent handling of it defies belief really.

There is no real difference between the way the British government handled the Bloody Sunday atrocity and the way Gulf Oil were allowed by our government to manipulate our community and dictate to our jurisdiction running roughshod over us and our dead.

My father was not around to carry out his duties to clean up the enormous mess left in Bantry Bay as the Betelgeuse spilled her Arabian heavy crude oil having split in two, exploded, and sunk at approximately 1am on January 8th.

Nor were his six local colleagues and friends who climbed the offshore jetty with him at 8pm, or the entire French crew of 42, and an English surveyor, Mr Harris, who boarded only 30 minutes before his death – all collectively involved in the biggest maritime disaster in the history of the Irish State.

My father now rests in the graveyard in the Church of Our Lady, Star of the Sea, and St Patrick in Goleen, his headstone reading ‘Victim of the Whiddy Island Disaster’, but he is not forgotten, nor those who he died with, nor will they ever be.

At 6am on January 8th, my mother had to sit me and my older sister Mary on her knee and tell us that ‘Daddy had gone to Heaven’ and then go and take down all my birthday balloons, and rebuild her shattered life. My younger sister Nora was only 5 months old.

While my mother was taking the balloons down, I was outside in my pyjamas. My mother came to the door and asked me what I was doing. I was letting go of some balloons and I said to my mother, clearly unaware then of the enormity of what had happened and how it would affect my life, “Mummy I’m sending these balloons up to make Daddy happy in heaven”.

In a disaster that should never have happened, the failures that took place – both on the ship, and at the oil terminal – were some of the worst derelictions of duty in relation to safety in world maritime history, by the tanker’s owners, (Total Oil SA); the terminal operators (Gulf Oil Corporation); the Irish Government, and other world governments.

It is the leading example of why doing nothing, having ‘fireside chats’ about what might or might not be a good idea regarding safety, while agreed international regulation by the world’s experts (including Ireland’s) at the International Maritime Organisation (IMO) fails to be ratified, putting innocent lives at risk, is not good enough.

Many lessons were learnt from the tragedy, but Dáil Éireann is still failing to act quickly enough, and more lives are being lost, as they again fail to ratify outstanding regulation that has been agreed at the IMO.

The 40th anniversary is a stark reminder of why it is so important to act, not just in Ireland, but internationally, as the world’s maritime community leaders descend on Bantry.

Simple inert gas sytems for oil tankers, to prevent explosion, had been agreed by world delegations and industry experts in 1974, when the IMO adopted ’SOLAS 1974’, but they were not carried on board the Betelgeuse because the convention had not then been ratified by enough national legislatures.

In the absence of regulation, best practice in industry was not applied.

After the Whiddy Island Disaster, Ireland ratified SOLAS 1974 and consequently the world brought it into force.

The failure to ratify SOLAS 1974 was compounded by the terrible safety regime that resulted in all personnel waiting for almost 30 minutes to die, with no fire equipment and no safety boat present. My father’s last words on the walkie talkie, recounted in the Whiddy Island Tribunal report, for me and my family to read were: “Quick, John, quick”, at 12:53am, preceded a few minutes earlier by “John are you on Channel 90 or 14?” and just before that, at 12:50, “John, where is the Donemark?”

The first witnesses saw the fire from the mainland at 12:30am.

The safety boat should have taken a maximum of seven minutes to arrive, and was even closer because it had just dropped off Mr Harris at 12:25am.

John Connolly, the dispatcher, was proven not to be at his post until it was too late, and along with him, the crew of the Donemark, the safety vessel, perjured themselves in the Tribunal.

This was hard for the families to take, on top of everything else. These people could have tried to swim and save themselves but relied on others – who then lied about it – and systems that failed them.

We would forgive them, but how is that possible if they do not tell the truth? It is mental torture. It has resulted in so many further tragedies amongst the French relatives, including suicide.

Readers can imagine the horror that greeted me when I read this in the library in University College Dublin on a dark November evening in 1996. It shocked me to the core of my being that no one had been held accountable for this dereliction of duty and betrayal by my father’s colleagues and employers. I had been shielded from this by my mother and my grandfather, but it started a process of mental torture. How could this be allowed to happen? Why were the French relatives kept away and treated so badly by Ireland? Why did our government not hold these people, their lawyers, and Gulf Oil management to account for fabricating the truth?

Our father was now gone, our beloved uncle was too, and so was our beloved grandfather, who I now realised in hindsight had known all this and died of a broken heart. The grief in that library that night was incalculable and I knew I would have to do something about it. Grief can be a very effective tool if used in the right way – if negativity can be turned into positivity, drawing hope out of grief’s toolbox.

The utterly cruel sacrifice of these people in our jurisdiction was therefore ultimate and unnecessary. But the families take solace in the fact that such a positive difference has evolved out of tragedy.

This sacrifice continues to have a profound impact on improving regulation today, and many lives have been protected.

Working first-hand in international maritime regulation, as a special advisor to the Arctic Council, having carried out reviews into international regulation with Lloyd’s of London, following the Deepwater Horizon rig and Costa Concordia disasters, and working on the finalisation of the hugely important Polar Code for world shipping at the IMO, I cannot emphasise enough the impact and importance of lessons learned from the Whiddy Island Disaster and the sacrifice of those who died and the positive change that it has led to.

We have developed a new forum and webportal for education and the implementation of regulation, at www.arcticshippingforum.is.

This has taken thousands of hours of voluntary effort and hard travel and diplomacy across the world.

I have presented this, with Norway, Kingdom of Denmark, and Finland on behalf of the eight Arctic states, to the rest of the world, as an example of how to implement regulation elsewhere, at the request of the IMO.

I have had to go to the well of my being to do this, out of duty to my father and those he died with, on behalf of all the families, and our community, here and in France, to give us hope and demonstrate that great things can come out of very sad situations, and no one is going to run roughshod over us.

In the absence of action by our government, I would have to go out and around them and work with other governments. I would succeed and would not take no for an answer. There was too much at stake for the foundation block of society – the difference between right and wrong, of respecting the law, or allowing corporations to violate it and crush the weak, and for the keystone of humanity – the protection of the young women of Ireland with small children, and their dead, in their hour of need.

This would not have happened were it not for the sacrifice of the life of my father and those he died with, and it is a development that Ireland’s current government should take careful note of.

As an acknowledgement of these world changes, the Canadian ambassador to Ireland, and representatives of Finland who chair the Arctic Council of States, along with other international leaders, will be in Bantry for the commemoration next week.

So will the RNLI, Irish Coast Guard, and relatives of Rescue 116, and all of Ireland’s maritime institutions.

What also makes the anniversary so important is that so many foreign people came into our jurisdiction and perished. One French family lost both parents, as the baker’s wife was on board visiting her husband.

A Dutch diver – Jaap Pols – was lost in the salvage operation, performed by the Dutch salvage company Smit Tak, at that time the most complex ship salvage project in history.

It is hard to explain the enormity of the pain that these people have suffered – 23 of the French bodies were never recovered, Bantry forever their resting place.

Supported by the French ambassador, many French relatives are making the difficult journey to Bantry.

Many of these relatives are ageing – wives, brothers and sisters of those who died, and it is so necessary for Ireland and our community to put our arms around them, particularly our maritime community.

Sadly, this is not something that has been supported appropriately by successive Irish governments. This does not require great leadership, but simple humanity and respect, and we have impressed this upon our political leaders in Ireland who have been invited.

This time will be different, we hope.

We are thrilled with the heartfelt support of community and in particular Cork County Council’s executive team.

Accordingly, it is extremely important that on January 8th we acknowledge these lives and highlight the importance of always adhering to best practice in the absence of regulation (throughout all industry sectors) and to implement agreed IMO standards in our jurisdiction, for the protection of our seafarers, and our environment, including our rescue services so that they do not have to be called out unnecessarily, thereby promoting world progress and implementation.

I would like to take this opportunity to thank Ireland’s maritime community, and the West Cork community, for supporting the work that I have been doing. In doing so you have been true and honourable friends of the sea and those that work there. The Southern Star’s articles have been read far from West Cork by governments and have also helped to influence change.

Many people have combined to ensure that, whilst we cannot bring back those who died at Whiddy Island, they are honoured for their sacrifice, which helps to protect our seafarers and rescue services, and our international environment today.

Bantry will no longer be remembered as a place of horrendous disaster and terrible shame but forever now as a place of hope that has saved many many lives across the world, where we, as children, of those who died, rose up, supported by our mothers and our local community, and influenced the world, so that those who died will, after Janaury 8th 2019, be immortalised for their sacrifice.

As a statement of that and these important issues, and remembering all in our seafaring community and rescue services who have died tragically, and those who assisted in and/or were affected by the disaster, we welcome everyone to Bantry for 11am mass and the wreath-laying ceremony afterwards in the Abbey Cemetery at the Memorial Monument.

• For more information, email [email protected] or [email protected]