A WEST CORK company has set about growing seaweed that could be the key to reducing the carbon footprint on Irish farms.

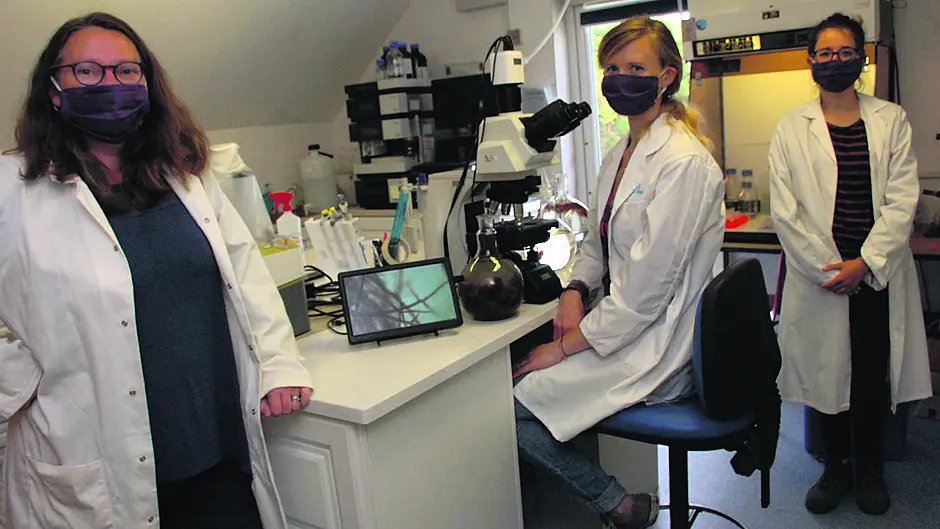

Situated on the shoreline overlooking Bantry Bay, Dr Julie Maguire and her team at the Bantry Marine Research Centre have successfully grown a seaweed that, when added to feed, reduces the methane emissions produced by cattle.

‘About four years ago, after reading a paper by Rob Kinley in Australia where he outlined a seaweed that was found to reduce methane emissions in cattle by up to 99%, with the support of BIM we set about screening some of our seaweeds in different locations to see if we could find one with similar properties to the tropical seaweed found in Australian waters,’ Dr Maguire told The Southern Star.

It was two years later when the team found a seaweed, Asparagopsis armata, which is very similar and of the same family as the tropical seaweed found in Australia.

‘This seaweed was first described back in 1942 by Mairín de Valera, the daughter of Éamon de Valera,’ Dr Maguire said. She was a professor of botany in UCG.

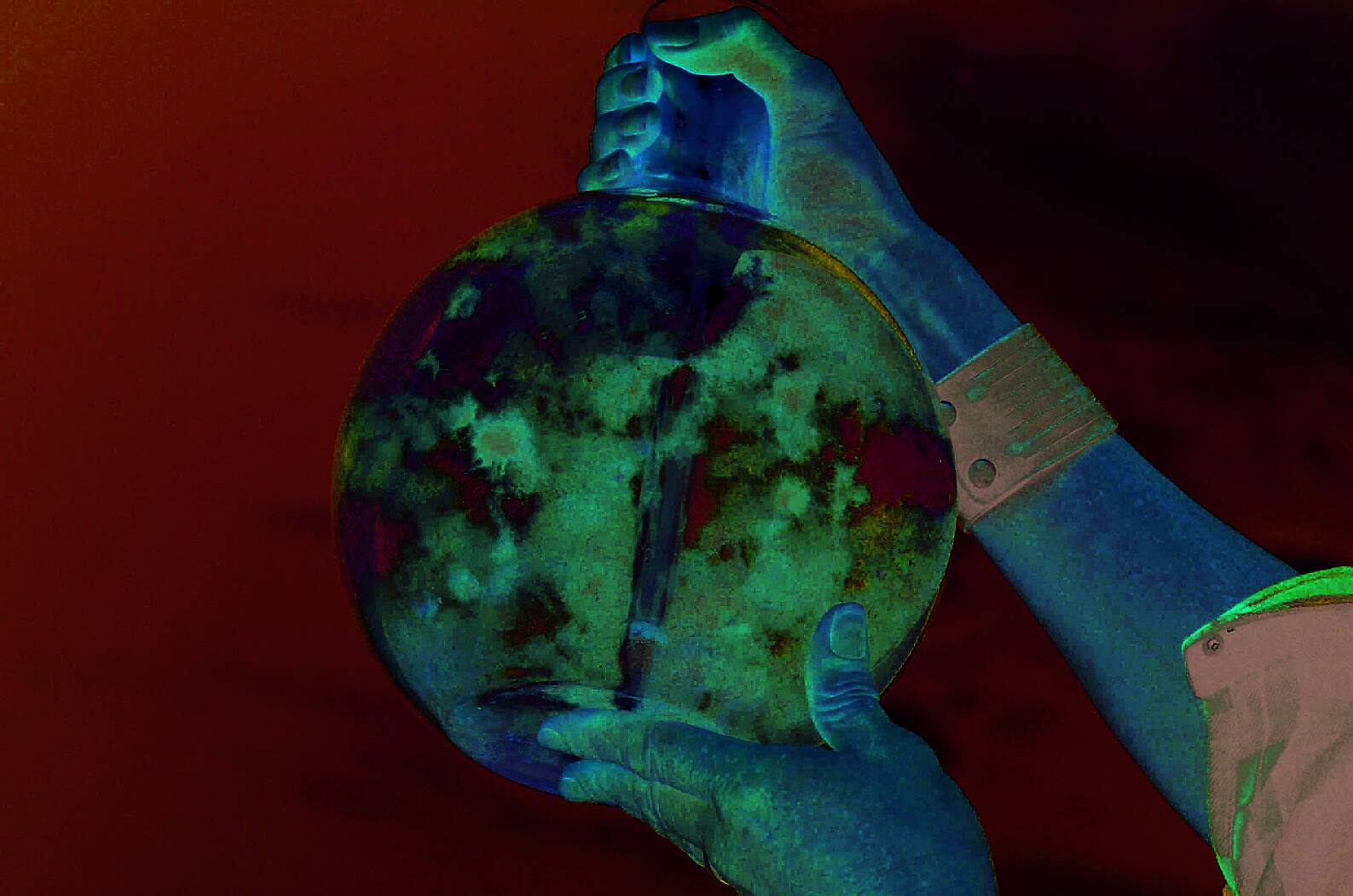

‘And so we started to grow the asparagopsis armata here on land at the research centre and our trials are well underway now.’

The seaweed known as asparagopsis armata was first described by Mairín de Valera, a former professor of Botany at UCG, and daughter of the late Eamon de Valera.

The seaweed known as asparagopsis armata was first described by Mairín de Valera, a former professor of Botany at UCG, and daughter of the late Eamon de Valera.

The plan is to produce an additive that, when combined with silage or dry feed, will reduce the methane emissions from cattle by up to 99%, a figure that would go a long way towards reaching the country’s carbon footpath obligations.

‘Most of the methane is produced in the first stomach of the cow, where the food is broken down and this process creates methane, so the addition of the asparagopsis armata changes the composition of the bacteria and produces other substances such as hydrogen and water,’ Dr Maguire said.

‘Right now we are growing the seaweed, so we want to get our biomass up, and as cattle eat up to 20 kilos day, we want to make sure that we have enough to start animal trials.’

‘There is great potential in working with seaweed. We have 600 species of seaweed around the coast and we don’t know what half of them are capable of, so there is a lot more work to do,’ she added.

A group of citizens recently won a landmark case against the Irish government for failing to take adequate action on climate change.

So, with the government under serious pressure to reduce its carbon footprint, the type of research being undertaken in Bantry could be a game-changer for Irish agriculture and also help the country to reduce its emissions in one fell swoop.