A new book by historian Tom Mahon tells the story of one of the most brilliant military actions to have ever taken place in Ireland. But it had dire consequences for Michael Collins and the emerging Free State

ONE hundred years ago in March 1922 – less than four months after the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty – Ireland teetered on the brink of civil war. Although the anti-Treaty IRA held sway over much of the countryside, Michael Collins, the chairman of the pro-Treaty Provisional Government, was methodically strengthening his position and gaining the upper hand.

Then like a bolt out of the blue the anti-Treaty IRA in Cork captured a Royal Navy arms ship, the Upnor, on the high seas. Coming ashore at Ballycotton they hauled away 80 tons of munitions, consisting of thousands of cases of rifles, machine guns, revolvers, ammunition and explosives. No wonder one of the ‘pirates’, Mick Murphy, exclaimed with delight: ‘the fecking war is over.’

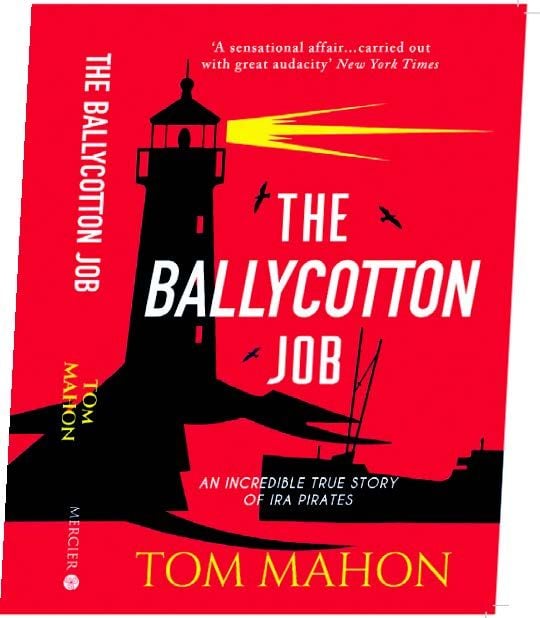

The Southern Star called the seizure ‘a sensation’, but the news resonated far beyond Cork; The Irish Independent referred to it as ‘an amazing exploit’, in London The Times reported the incident as ‘a clever and daring coup’ and even the New York Times remarked that it was a ‘sensational affair…carried out with great audacity.’

At a stroke Michael Collins and his government appeared highly vulnerable and the fate of the Treaty hung in the balance. There was consternation in Whitehall, where the authorities wrongly blamed Tom Barry, the commander of the legendary West Cork Flying Column. General Nevil Macready, the outgoing British commander in Ireland, compared the panic in Downing Street to the outbreak of World War One: ‘The declaration of war in 1914 was as nothing to the wild excitement consequent on the capture of Mr. Barry of one of His Majesty’s ships of war.’ Macready worried that: ‘this seizure turns the balance heavily against the Provisional Government.’

However, no one was more shocked than Michael Collins. When Macready met Collins he ‘found him in a very anxious frame of mind.’ Though he sarcastically added: ‘Poor Michael is distressed that we turn over arms to Mr Barry of Cork from a “man of war” and we won’t give him any.’

Collins was furious with the Royal Navy’s inability to safeguard the arms, but he also suspected British duplicity, complaining to Winston Churchill the Secretary of State for the Colonies, about ‘how desirous certain sections of the English military authorities were to arm Irish men against each other.’ He elaborated: ‘It is generally believed here that there was collusion between those responsible on your side and the raiders. Also generally believed that the capture was enormously larger than [you stated].’ He was wrong on the first point, but right on the second.

For once Churchill was forced to backdown and he grudgingly admitted the navy bore responsibility, though he denied any collusion. Churchill, knowing that Collins was the only Irish leader capable of implementing the Treaty, solicitously cautioned him: ‘I trust you will remain as much as possible at the centre of affairs and not expose yourself more than is necessary…[I have been informed that] attempts are designed against your life.’

At the same time he authorised the British army to supply Collins’ recently formed National Army with 8,000 rifles, 4,000 revolvers and 20 Lewis machine guns. This was a decision that led further down the road to civil war, which broke out less than three months later when the National Army attacked the IRA garrison in the Four Courts in Dublin.

The Civil War resulted in, almost as many deaths as the War of Independence, the destruction of much of the country’s infrastructure particularly in Cork and left a legacy of bitterness that persisted for over 50 years. The arms and ammunition from the Upnor played a crucial role in the carnage. A senior British civil servant admitted: ‘By this mischance [the taking of the Upnor] the rebels got vast stores of ammunition and prolonged their resistance.’ While a leading official in the Dublin government complained: ‘If the British forces had not negligently permitted the capture of this vessel by the republicans the latter forces would have been much more easily suppressed.’

One of the greatest tragedies of the war occurred on 22 August 1922 when Michael Collins was ambushed and killed at Beál na Bláth. Given that the majority of the Cork IRA’s weaponry came from the Upnor it’s more than likely that the rifles used in the ambush and the bullet that killed him were from the haul.