In the first of a two-part series Tom Lyons highlights the important role that the railway played in the early days of GAA in West Cork

*********

RECENTLY they buried a huge part of GAA history in Dunmanway when they laid Finbarr Hennessy, one of the greatest club men West Cork has ever produced, to rest.

The timing of Finbarr’s passing was ironic, as he was an employee of CIE all his life and it is exactly 60 years since CIE itself buried a huge part of West Cork history, including GAA history, when they closed down the West Cork railway system on Good Friday, March 31st, 1961.

The largest civic protest in the history of the state failed to reverse the closure and, at the stroke of a pen, a way of life was wiped out here in West Cork.

In this article we deal with the influence the railway had on the growth of the infant GAA in West Cork in the closing years of the 19th century. Without the trains it is doubtful if Gaelic games would have survived those early, turbulent years and trains continued to greatly influence West Cork GAA right up to the closure in 1961. It could be argued that the trains and the GAA had their golden era in the 1950s here in West Cork when thousands of supporters availed of the train excursions to travel to matches, especially in Cork city.

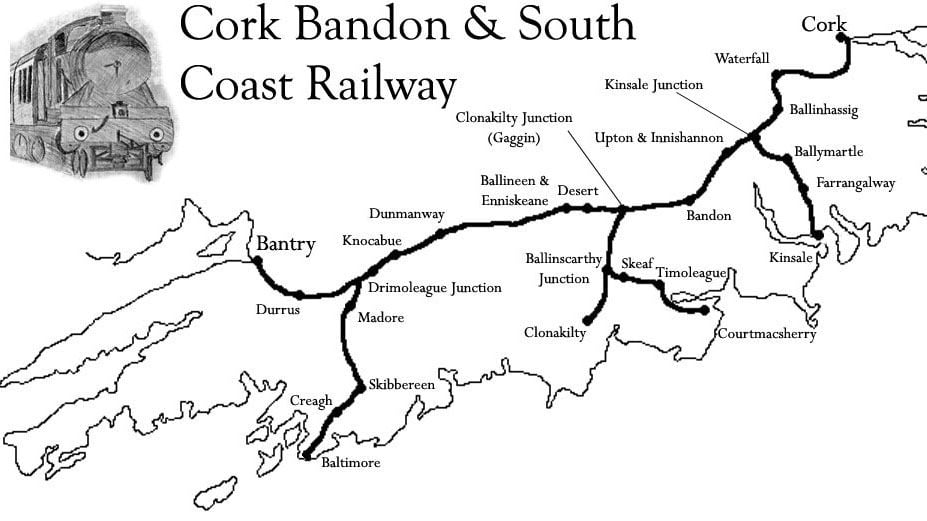

It all began in 1849, in the height of the Great Hunger, when the first branch of the West Cork railway was opened from Bandon to Ballinhassig, almost 40 years before the arrival of the GAA. In 1866 the railway reached Dunmanway, 1877 Skibbereen, 1881 Bantry and 1886 Clonakilty. It was no coincidence that the GAA first blossomed in West Cork in 1887.

The pioneering members of the infant GAA in West Cork in the early years had a number of huge difficulties to contend with before the association got a firm footing in the region. First was the anglicization of the people as English culture and sports swept the country. Gaelic games, especially hurling, had died in many areas, including most of West Cork. A rough and ready game of football, called caid, was played in a few areas like Rosscarbery and Kilmacabea.

Secondly, persuading the locals to accept a new set of common GAA football rules was not easy and led to much friction between local teams. No championship hurling was played in West Cork until 1905.

Thirdly, poverty and hunger were no strangers in West Cork following the Great Hunger and right into the 1890s a series of potato blights swept West Cork, especially along the coast, causing great hardship among the peasant classes. It was those same peasants who were to backbone the new GAA.

The Cork, Bandon and South Coast Railway played a large part in promoting the GAA in West Cork from 1890 on.

The Cork, Bandon and South Coast Railway played a large part in promoting the GAA in West Cork from 1890 on.Fourthly, because of the grinding poverty, emigration was a huge problem in most areas, many districts being stripped of their young men who would have been players on the new football teams

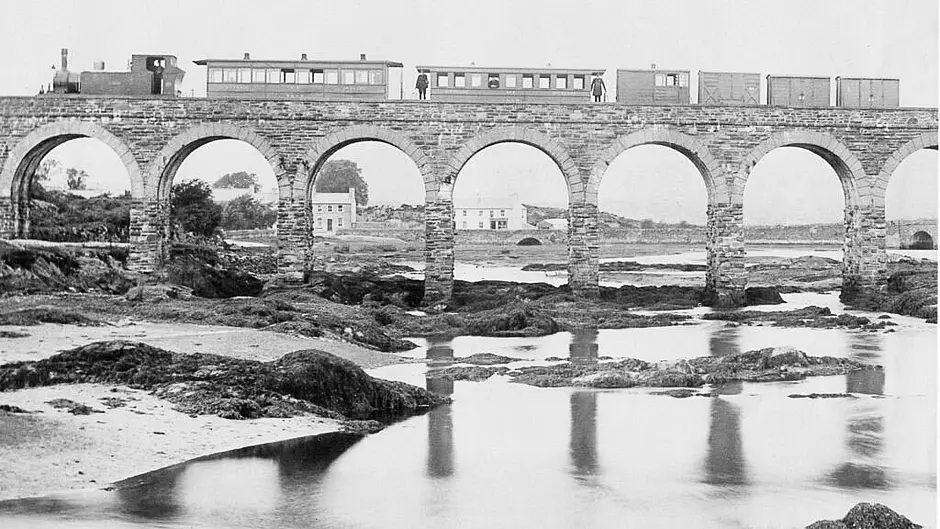

Fifthly, and this is where the railway came to the fore, travel difficulties were probably the biggest problem for any area hoping to set up a GAA team. Roads were scarce, especially when one travelled away from the coastline, and the few roads that existed were badly maintained. People rarely left their own districts and walking was the main way of travel. The early teams used wagonettes to travel to games but these were open to the weather and slow. Players then had to change into playing gear on the field of play and change back into wet clothes after the game. Little wonder we often read of players in their prime dying of pneumonia and related diseases.

Supporters had to travel by foot, horseback or pony and trap and, as a result, while teams were set up in many townlands, they usually only played neighbouring townlands in challenge games. Very few bothered to affiliate to the GAA itself and never played in championships. The few teams that did play championship football found they had to travel to Cork city, usually to Cork Park where Páirc Uí Chaoimh is now situated, to play their games. That was practically impossible for most rural teams in West Cork.

Without the railway, it is doubtful if the GAA as an association would have secured a foothold in West Cork in the 1880s and 1890s. Only a handful of West Cork clubs affiliated to the GAA and played in the championship and most of those were the urban town teams that were on the new railway line. Clonakilty, Dunmanway, Skibbereen, and Bantry were the pioneers in 1888, the first championship to be played by West Cork teams. Bandon was slower to join in, in 1892, because rugby was the dominant game in that strong garrison town.

Those town teams used the train to travel to Cork to play games. Just how important the trains were to the early GAA was shown in the founding of the Timoleague GAA Club in 1892 by railway workers who arrived in the area with the new railway line to Courtmacsherry. The station master, John Burke, was the first secretary of the new club and was to become one of the foremost GAA men in West Cork in the 1890s.

In Bandon, it was also the station master, David O’Brien, who was president (chairman) of the new GAA club and all through the 1890s he was the West Cork representative to the county board and was one of five Cork delegates to the National Convention in 1893. He played a major part in the big railway strike of 1898.

The two main exceptions to the above trend were Kilmacabea and Rosscarbery (Carbery Rangers), who were not on the railway line. They had very strong teams in those early years because of their history in the old-time caid football. In order to travel to games in Cork, they took wagonettes to either Skibbereen or Clonakilty, where they would board the train to Cork. Plans were formulated to run railway lines to both Rosscarbery and Glandore but nothing ever came of them.

It is worth noting the difficulties associated with train travel for those early teams. Firstly, was the cost, as even third-class tickets were outside the reach of many players, at a time of high unemployment when money was scarce. Secondly, clubs had to hire special excursion trains to accommodate their players and supporters and had to pay up front for those excursion trains. There was no guarantee of a crowd, so clubs were financially at risk at a time when they didn’t have any club funds and fundraising was unknown.

Thirdly, time-keeping was a huge problem in those early days of the GAA, games often starting hours late. In some instances, where West Cork teams travelled by train to Cork, they found games already being played on the field and running so late that they had to forego their game in order to be in time for the return train home. In one instance we find the Dunmanway team having to walk 20 miles to get home, having missed their train.

The original train company in West Cork was the Cork and Bandon Railway but that was changed to the Cork, Bandon and South Coast Railway in 1888. That company was to play a large part in promoting the GAA in West Cork in later years. In 1924, in the new Irish state, that company became part of the Great Southern Railway, which, in turn, was to form Córas Iompar Éireann (CIE) in 1945.