There are moments on weekends like the one I just had, where I genuinely wonder why we don’t move to the country altogether.

This is the curse of the city dweller: longing for a picture-postcard version of a place on a sunny weekend away, then projecting all sorts of possibilities onto it.

Move here. Buy a cottage. Write columns from a kitchen table overlooking Slea Head. Teach the kids to surf and forage, to be wild and free.

Cities wear you down in a thousand tiny ways. Out on the Dingle Peninsula last weekend, life felt stretched out and properly savoured.

When I booked my ticket for the Ride Dingle cycling event months ago, I had the choice of two routes: a relatively civilised 55km spin around Slea Head, or the full 120km adventure which takes in Slea Head and a steep ascent up the Conor Pass.

Naturally, I went for the 120km option. Naturally, I also intended to train properly in the meantime.

But life, or more accurately, home renovations (and my own general uselessness), intervened. Beyond five or six half-hearted spins around Howth Head in Dublin, and a major one over Wolftrap Mountain in Offaly, I had nothing close to the kind of conditioning needed for 120 kilometres and 1,700 metres of climbing.

Still, optimism (or denial) is a powerful thing. And so there I was at 8am on Saturday morning, clipped in at the Dingle Marina with my brother-in-law and hundreds of others, waiting for the countdown to Ride Dingle to begin.

We set off under a brightening sky, a rolling wave of wheels and bright jerseys moving out of town in a spirit of positivity and celebration.

We pedalled out past Ventry, past the white gable of Páidí Ó Sé’s bar, stretched out in a long bright chain.

And then Slea Head: the road was closed to traffic, the cliffs dropping sheer to the Atlantic below, ancient beehive huts perched above the fields. Past the gloriously daft, ‘Hold A Baby Lamb’ signs, around vertigo-inducing corners where you felt you could almost reach out and touch the sea.

At times, with the mist lifting off An Fear Marbh and stone huts clinging to the hillsides, it felt like cycling through a trailer for Star Wars, only with high-vis jackets instead of lightsabers. (By the way, if the Force was strong anywhere, it was in the legs of the lads who flew past me doing 40kph on the steep sections. Weetabix had been consumed, it seems.)

Although the cycle gave us the best morning of the weekend, the weather was otherwise as chaotic and unpredictable as a typical south-west coast forecast. We stayed in a small Airbnb cottage near Ballydavid. Every time you opened the front door, the weather didn’t just greet you — it entered the kitchen, shook itself off, and made itself at home. I found my mind drifting back to olden times, when people lived out here in stone houses with thatched roofs and barely a window, sharing a room with three generations and some livestock, most likely. How hard life must have been before Ryan’s Daughter sprinkled its movie magic around the place and kickstarted an entire tourism industry.

When we arrived on Thursday, we made a few smart remarks about how the little cottage didn’t seem to take advantage of the majestic view of the Three Sisters in the bay beyond. After a few hours of gales and sideways rain, it became perfectly clear why. These houses weren’t built to admire the scenery. They were built to survive it.

However, the sun was shining by the time we hit the Conor Pass ascent and the group had splintered into small clusters, each of us locked into our own private battles with gravity. Every time I rounded what I thought must surely be the final corner, another would reveal itself: steeper, longer, laughing at my straining calves. Sheep chewed lazily along the verges, casting the occasional pitying glance.

Somewhere halfway up, I stuck in my earbuds and put on Cormac Begley’s eponymous album for moral support. There’s no better soundtrack for an uphill battle. His playing of the bass concertina sounds less like a man serenading an audience, and more like someone trying to wrestle a wild animal — the instrument straining at the leash of its traditional moorings, threatening to slip the harness altogether and escape into free-form jazz. It felt fitting.

I finally made it to the summit and after a brief stop to admire the views, I had a wonderful freewheel down into Camp; the beautiful descent after the hard climb is one of the true thrills of cycling. With 90 kilometres under my belt and lungs like Begley’s concertina, I decided to quietly opt out of the final 30km slog back to Dingle. The last leg looked like it had been mapped by Mick O’Dwyer planning winter training in 1984. Sometimes you have to know when to quit. ‘Learn to listen to your body’, the wellness brigade advises. And my body was most definitely shouting, in a loud Kerry accent: ‘Will ya shtop, lad!!’

Happily, my wife came to collect me. At that stage I was a man who needed a lift more than a yellow jersey. There’s no shame in knowing your limits, and the thought of fish and chips and a cold pint down the road seemed like a deserved reward.

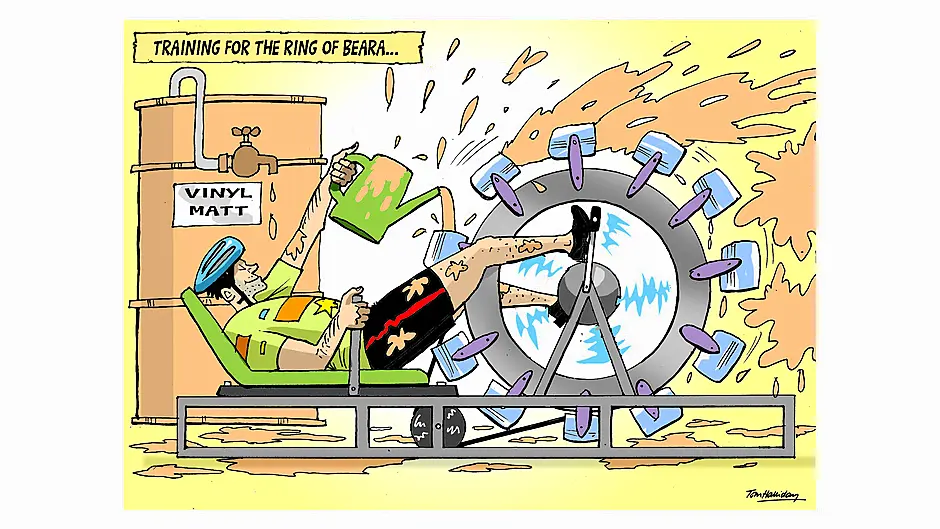

We’ve another spin lined up for the Ring of Beara in a month, which is even longer, and where we’ll hardly get this lucky with the weather again. I really should start training for that one, shouldn’t I? I will. Tomorrow. (Unless, of course, the kitchen needs painting.)