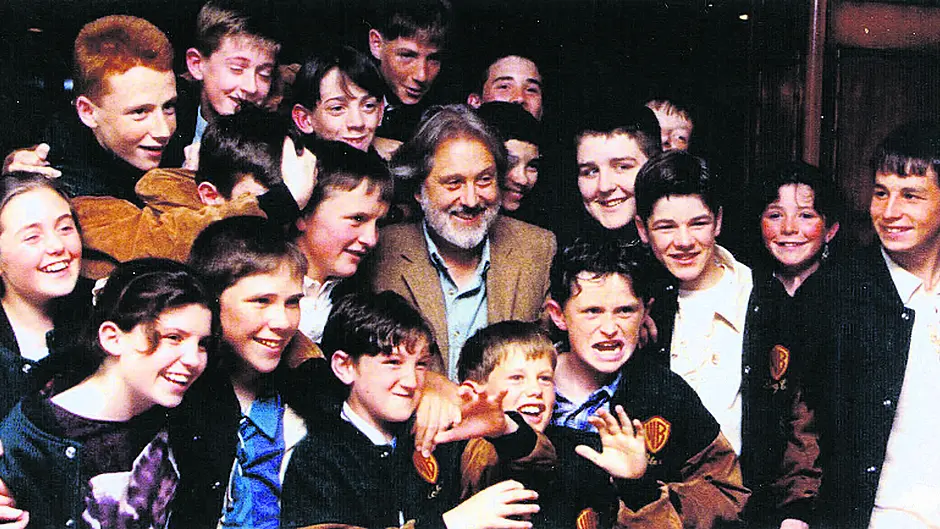

At least three of the local young people who worked on the movie have since gone on to make film their career, producer David Puttnam tells Niall O’Driscoll

WHEN holidaying in West Cork in 1988, producer David Puttnam stumbled upon a house near Skibbereen that he and his wife Patsy subsequently came to call home.

It was a significant moment, not only for the Puttnams, but for West Cork too.

A few years later, Puttnam chose West Cork as the location for a remake of La Guerre des Boutons, an old French film which, at first, seems to be little more than a simple tale of two rival gangs of children. Scratch the surface, however, and one quickly realises the darker commentary it makes on human life itself.

‘Bearing in mind that at the time there were still tensions on both sides of the border with Northern Ireland,’ he explained, ‘it struck me that this was an opportunity to make a film that was a metaphor for what was going on – which, the more I lived here, the less sense it made to me.

‘This concept, as a metaphor, has been around for a very long time and it was originally applied to World War II. In fact, it might even have been earlier – I’m not sure when the original book was published – I think in the 1930s. It’s about people fighting over something that their fathers fought over, and their grandfathers fought over, yet none of them actually know what it was.’

‘The bridge at Union Hall (which features prominently in the film) I saw as the equivalent of a demarcation line, like the peace lines in the North, and it struck me that that was useful. I got a writer that I’d worked with before on Chariots of Fire and other things – Colin Welland – to come down and we walked and drove around and talked about what might be. We had the original movie to go on, which obviously was hugely helpful, and we took it from there.’

David had originally moved to West Cork in a conscious attempt to step out of the movie industry limelight, yet by making a film on his doorstep he put himself back in the spotlight. ‘Well I was warned, not so much by people from around here, but by people in London, that that’s exactly what I was doing and that I was in danger of taking the very thing that I’d looked for – which was peace and quiet – and transforming it into work. It didn’t really work out that way, though. The film was very pleasant to make. It was the first time in my life that I was actually able to work and live at home, which was lovely. It was a very nice experience.

‘The advantage was that I was living in an area that I knew – and so it was very easy for me to talk to people when I needed a bit of help. We made a decision very early on to use as much local labour as we could, and where possible, to get young people into assistant jobs. Interestingly enough, I think at least three of them, maybe more, have ended up with careers in the industry, having had their first apprenticeships on that film.’

Although he has taken a bit of a step back from the film industry in recent years, he agrees that certain subjects renew his interest. ‘Films are like having a conversation. You’re trying to say something. In the War of the Buttons I was trying to say “just look again at what it is you’re doing here and ask yourselves the question of why”. Every movie I’ve ever made, in some way, shape or form, has been trying to ask a question. If I felt there was a really compelling question, that I felt making a movie could help answer or throw some light on, then I think I’d be very inclined to give it a go.’