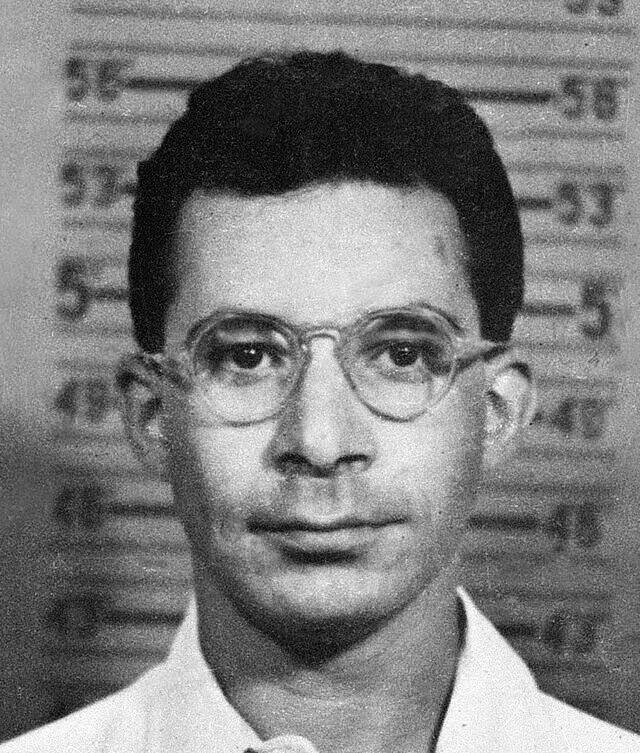

On May 21st, 1946, Canadian scientist Louis Slotin was demonstrating a nuclear experiment to his replacement, Alvin Graves, in the Los Alamos laboratory New Mexico.

Slotin had worked on the Manhattan Project alongside J Robert Oppenheimer, developing the world’s first nuclear weapons.

The project’s success culminated in the detonation of the first atomic bomb in July 1945, changing the course of World War II.

But with the war over, Slotin had decided it was time to leave the Manhattan Project and return to teaching.

That afternoon, Slotin was performing a procedure ominously nicknamed ‘tickling the dragon’s tail’.

The experiment involved using a screwdriver to manipulate two beryllium hemispheres surrounding a plutonium core, demonstrating how close the setup could come to criticality, the point at which a nuclear chain reaction begins.

During the experiment, Slotin’s screwdriver slipped, causing the beryllium hemisphere to fall. This triggered a burst of radiation, visible as a distinct blue flash.

Slotin shielded his colleagues, taking the brunt of the radiation while absorbing twice the lethal dose.

Aware of his fate, he quickly sketched a diagram of where everyone had been standing to help future researchers understand how radiation exposure affects the human body.

Nine days later, Slotin succumbed to his injuries, his body devastated by the effects of acute radiation poisoning.

Canadian scientist Louis Slotin.

Canadian scientist Louis Slotin.

Slotin’s story is a reminder of the incredible power, and danger, of radiation.

But he was not its first casualty. Decades earlier, Marie Curie, the extraordinary scientist who pioneered research in radiation, succumbed to a blood cancer caused by her groundbreaking work.

She was the first woman to win a Nobel Prize, earning one for physics in 1903 and another for chemistry in 1911.

Curie revolutionised medicine, making it possible to diagnose diseases and even treat cancer with radiation.

However, this same force that transformed medicine still carries significant risks.

Radiation is all around us.

It comes from the sun, some medical scans, and even the ground beneath our feet.

It may have been discovered just 130 years ago, but its story began with the birth of the universe.

In Greek mythology, Uranus, the god of the heavens, was overthrown and buried deep within the earth by his son, Kronos.

Ancient mythology says that he lay far under the surface of the earth, bitter and festering, concentrating all his anger and power into the metal around him, waiting for a time to release it.

The name given to that metal? Uranium.

Polish-French physicist Marie Curie.

Polish-French physicist Marie Curie.

We know now that as uranium decays it does release an odourless, invisible gas called radon.

Radon seeps into buildings through cracks in floors or gaps around pipes, often without anyone realising it.

A silent intruder, radon is one of the leading causes of lung cancer, linked to approximately 350 cases in Ireland annually.

For smokers, exposure to high radon levels increases the risk by 25 times.

Unfortunately, Ireland has some of the highest radon levels in Europe, with areas like Cork and Kerry particularly vulnerable due to their geology.

Some homes have been found with radon levels far exceeding the safe limit of 200 becquerels per cubic metre (Bq/m³).

In 2003, a house in north east Kerry recorded an extraordinary 49,000 Bq/m³, 185 times the acceptable level.

North Cork has also been identified as a high-risk area.

Fortunately, testing for radon is simple and affordable. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) website provides a detailed free radon map where you can check your area by entering your Eircode.

Then, for about €50, the price of a night out at the cinema for two, you can order a radon testing kit for your home.

If high levels are detected, specialists can install ventilation systems, membranes, or turn on radon sumps to help reduce exposure and protect yourself from this invisible danger.

Know the facts – own your risk – decide for yourself.