This article originally appeared in our KILMICHAEL AMBUSH CENTENARY SUPPLEMENT which can be read in full here.

--

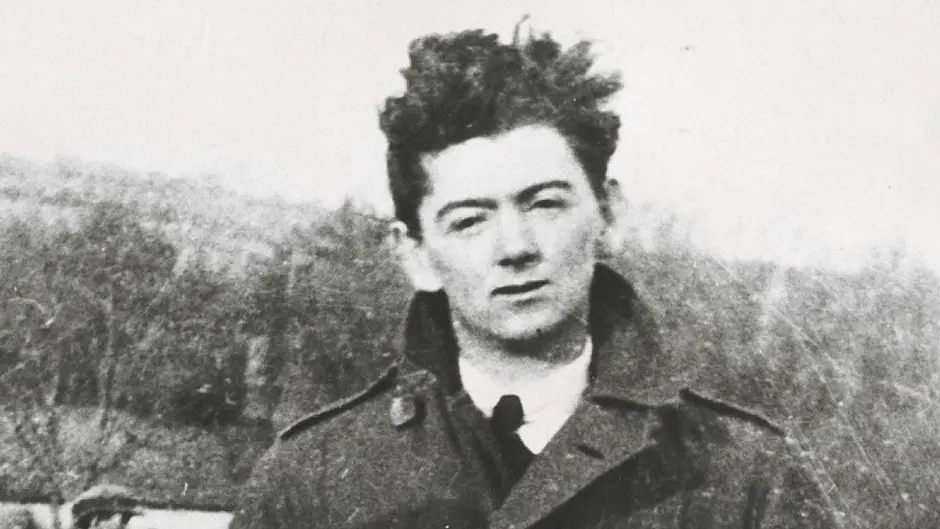

GROWING up in Dunmanway in the 1960s, we were truly immersed in the exploits of the legendary Boys of Kilmichael and their leader, Tom Barry, was – in our impressionable young minds – ranked as a veritable deity.

His book, Guerilla Days in Ireland, was regarded as the bible of the War of Independence in West Cork. No wonder I was in awe when I first met Tom Barry at about the age of 10 when the 50th anniversary commemorations of the 1916 Rising were going on followed by the same milestone for the Kilmichael Ambush in 1970.

It was in the bar of the Victoria Hotel on Patrick Street in Cork that my father, Sgt Jim Downing, who would have been familiar with Barry from being on duty at the annual Kilmichael commemorations over the years, introduced me to the man himself who exuded a sort of regal aura as he held court in the intimate room which he frequented with his wife, Leslie Bean de Barra, who also played a big part during the revolutionary years and was a quiet, dignified and gentle woman. It always struck me on seeing them together on various occasions subsequently what a fine couple they made with their personalities complementing one other.

While Barry seemed to enjoy the attention and reverence he got from people at the time, one could also detect a steely side to his character and that he was not one to suffer fools gladly.

One thing that stood out for me was the amount of cigarettes Tom Barry smoked. He used a cigarette holder, which was a form of filter that was a fad at the time.

He was an affable character who had no problem making small talk, be it to other adults or to a young fellow like myself that I sense he knew was slightly in awe of him, but he still managed to put me at ease in his company. While Barry seemed to enjoy the attention and reverence he got from people at the time, one could also detect a steely side to his character and that he was not one to suffer fools gladly.

British Army

So, where did the enigmatic Tom Barry emerge from? He was born in Killorglin, Co Kerry, on July 1st, 1897 and was the son of an RIC officer, Thomas Barry snr, who quit the police force in 1901 and returned to his native Rosscarbery to set up a business.

Young Tom was sent to boarding school in Mungret College, Limerick, but was not an academic type and he ended up enlisting in the Royal Field Artillery regiment of the British Army in Cork in the summer of 1915, where he received the military training that he was later to use against Crown Forces. Early the following year, Barry and his colleagues were posted to the frontline in Mesopotamia (which included most of what is now Iraq) and he was promoted to the rank of corporal. But, after hearing about that April’s 1916 Easter Rising back home in Ireland, he resigned in protest and reverted to being a gunner.

In Guerilla Days in Ireland, Tom Barry wrote: ‘It was there, in that land of the Arabs, then a battleground for the two contending imperialistic armies of Britain and Turkey, that I awoke to the echoes of guns being fired in the capital of my own country, Ireland. It was a rude awakening, guns being fired at the people of my own race by soldiers of the same army with which I was serving.’

For Barry, the Great War dragged on as 1917 saw a return from the borders of Asiatic Russia to Egypt, Palestine, Italy, France and, in 1919, to England. ‘Back to Ireland after nearly four years’ absence,’ wrote Barry, ‘I reached Cork in February 1919. In West Cork I read avidly the stories of past Irish history.’

Impressed

What impressed and inspired Tom Barry most then was the 1916 Proclamation: ‘The beauty of those words enthralled me. Lincoln at Gettysburg does not surpass it, nor does any other recorded proclamation of history. Through it shines the grandeur and greatness of those signatories who were about to die with their pride, their glory and their faith in their long-conquered people.’

In Barry’s estimation, of all the events since the Rising of 1916, by far the most important was that which naturally followed the Republican victory at the general election of 1918, the proclamation of Dáil Éireann setting up the government of the Irish Republic as the de facto government of Ireland in January 1919.

‘The Rising of 1916 was a challenge in arms by a minority,’ he said, ‘This was a challenge by a lawfully-established government elected by a great majority of the people. The national and the alien governments could not function side by side and one had to be destroyed. All history has proved that, in her dealings with Ireland, England had never allowed morality to govern her conduct.

‘Force would be used to destroy the government of the Republic and to coerce the people into the old submission. There could be no doubt it would succeed unless the Irish people threw up a fighting force to counter it.’ Barry had found his calling.

He made enquiries locally in the middle of 1919 about how to get involved with the Volunteers who were mobilising again and got in touch with Sean Buckley of Bandon. However, because of Barry’s involvement with the British Army in the Great War, the local IRA were understandably wary of him – especially Tom Hales who distrusted him – and they wanted him to prove his revolutionary credentials in a practical sense.

Buckley encouraged him to maintain his links with ex-servicemen’s organisations and to act as an intelligence officer, gleaning information from the British military and their supporters in the Bandon area. He was told not to parade with the local Volunteer company, so he was very much an unknown quantity.

Barry’s expertise in training what were effectively raw recruits and imposing military discipline were crucial in the success of his side’s guerrilla warfare tactics, which gave them the edge over what, on paper, should have been far superior British forces.

Kilmichael

Barry was only 23 when the Kilmichael Ambush took place, but he showed a maturity beyond his years in planning it and executing it. The word executing is apt in this context as he saw it as a fight to the death between his flying column and the Auxiliaries, which contributed the controversy about the ‘false surrender’ being claimed as bogus, created by revisionist historian Peter Hart, caming into being in his 1998 book.

The late Canadian history professor also alleged that, during the War of Independence, the IRA – driven by sectarian Catholic motives – carried out ethnic cleansing of Protestants across West Cork. However, Barry refuted this, admitting that they took a hard line on people he believed were collaborators with the British forces and stating that his unit shot dead 16 civilians accused of informing in the first six months of 1921.

He acknowledged that nine of the 16 killings were of Protestants, who were a minority in West Cork. Barry maintained that they were killed for no other reason than for their aid to British forces, pointing out: ‘‘The majority of the West Cork Protestants lived at peace throughout the entire struggle and were not interfered with by the IRA.’

Hart’s theories are still championed by a small cohort of historians and journalists to this day, however Con O’Callaghan, former chairman of the Kilmichael & Crossbarry Commemoration Committee, was keen to point out what he regards as ‘a clear admission that there was a false surrender’ in the memoirs of Brigadier General Crozier, who was in charge of the Auxiliaries in Ireland. He wrote of the Kilmichael Ambush: ‘The correct story I found to be as follows; The lorries were held up by land mines and the leading lorry was partly destroyed. The men were called upon to surrender and did so throwing up their hands and grounding their rifles.

‘Each policeman carried a revolver in addition to a rifle. One policeman shot a Sinn Féiner at close quarters with his revolver after he had grounded his rifle and put his hands up.’

Issuing instructions before the ambush, Barry had warned his troops that the positions they were about to occupy allowed for no retreat, ‘the fight could only end in the smashing of the Auxiliaries or the destruction of the flying column.’ He emphasised that ‘this would be a fight to the end, and would be vital not only for West Cork, but for the whole nation.’

During the Civil War, Tom Barry took the Anti-Treaty side and maintained his staunch republican ideals throughout his lifetime.

Looking back, Barry later wrote: ‘They said I was ruthless, daring, savage, blood thirsty, even heartless. The clergy called me and my comrades murderers; but the British were met with their own weapons. They had gone in the mire to destroy us and our nation and down after them we had to go.’

He died on July 2nd, 1980 – the day after his 83rd birthday.

• Con Downing is editor of The Southern Star