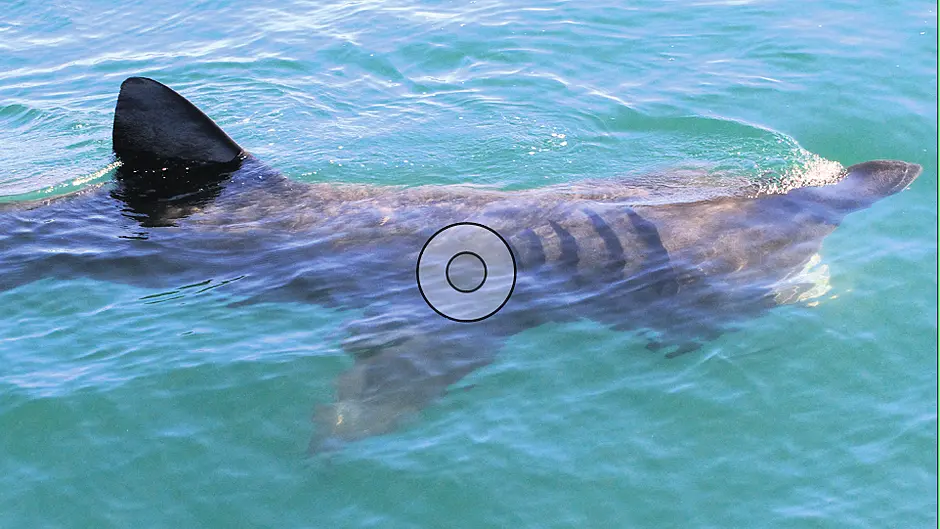

EARLIER this month, the marine biology world had its attention turned to the very unusual appearance of a smalltooth sand tiger shark on the shoreline at Kilmore Quay in Co Wexford. This was an exciting find as the species had never been recorded in Irish waters before, with the Bay of Biscay being its northern limit.

Due to the extraordinary nature of this stranding in Ireland, marine and shark biologists from Trinity College rushed to the scene to examine the shark and to take samples for analysis. Scientists are keen to learn as much as they can about this unfortunate animal because it is the second smalltooth sand tiger shark to come ashore recently, with a first stranding occurring just last month in Hampshire, UK. Despite measuring 14 feet long, reassuringly this species does not pose a threat to humans.

It is, as yet, a mystery as to why these animals stranded outside of their usual range but also a worrying one because the species is listed as ‘vulnerable’ by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

Mermaid’s purses

On the subject of sharks, just before Easter (as part of an egg theme) I spent some time in St Patrick’s Boys’ National School in Skibbereen talking to the boys about mermaid’s purses and where they come from. Mermaid’s purses are the common name for the empty shark and ray egg cases that often wash up on our coastline. Shark reproduction methods vary and only some shark species, such as the small spotted catshark and the nursehound, produce eggs that develop externally and therefore by definition are oviparous. Other species are either oviviparous, protecting the eggs internally until they hatch and the shark releases live young, or viviparous giving birth to live young that have developed internally, like mammals, nurtured by an umbilical chord.

The most common shark egg case we find in West Cork is that of the small spotted catshark, also known as the lesser-spotted dogfish. These sharks usually lay their eggs offshore amongst seaweed. The egg is surrounded by a thick and tough keratin case which has curly tendrils which wrap around the stalks of seaweed, such as kelp, to anchor it in place while the embryo develops. It is both lovely and interesting to find evidence of these shark births by spotting the vacated egg cases on the beach. You can also record your sightings on Purse Search Ireland to help inform the location of nursery areas for Ireland’s egg-laying sharks, skates and rays.

Sharks in Irish waters

With the stranding of an unusual shark this month and the school discussion about the shark egg cases, this made me wonder exactly how many shark species there are in our waters. According to the Irish Elasmobranch Group, 39 species of shark have been officially recorded in Irish waters as of February 2023. Therefore, if they are satisfied to add the smalltooth sand tiger shark seen this month, this brings the total to 40. This is quite an impressive number and is due to our location on the edge of the continental shelf which provides a range of unique and diverse habitats.

However, of those 40 species of shark, three species are classed by the IUCN as ‘critically endangered’, three are ‘endangered’ and four are ‘vulnerable’ with many more classed as ‘near threatened.’ The main threats to sharks are by-catch in commercial fishing, overfishing, habitat loss due to pollution and human activity and climate change.

A small spotted catshark egg case washed up on Long Strand at Castlefreke, still attached to a kelp stalk. (Photo: Ann Haigh)

A small spotted catshark egg case washed up on Long Strand at Castlefreke, still attached to a kelp stalk. (Photo: Ann Haigh)

Basking sharks

One of the most exciting sharks we have off our coast is the basking shark (Cetorhinus maximus) which is one of our species that is listed as ‘endangered.’ Basking sharks were driven to the edge of extinction due to hunting and overfishing in the 1950s and their recovery has been slow due to their long reproductive cycle. However, there was great progress in October last year when the government finally granted legal status to basking sharks as a ‘protected wild animal’ under Section 23 of the Wildlife Act. The new regulations make it illegal to hunt, injure or interfere with them and covers protection for their breeding and resting places.

Every year in the spring basking sharks start to appear off our coastline. These giants may reach lengths of nearly 40 feet, weights of 4 to 6 tonnes and can live for up to 50 years. They may arrive as early as February, but it is usually April when the first local sightings are reported and numbers increase over the summer months, peaking in June. The timing of their arrival coincides with microscopic algae and zooplankton levels in the water. Rising sea temperatures cause these to flourish and this attracts the basking sharks which gently filter the water to feed on zooplankton. This is done via a process known as ‘ram feeding.’

The giant sharks swim slowly close to the surface of the water, “basking’’ with their huge mouths gaping. As they move, they constantly funnel water through specially modified feeding gills known as gill rakers and it is estimated that they filter around two million litres of water per hour.

One fact that has always stuck with me, is that unlike many other shark species, basking sharks cannot suck or pump water through their gills and therefore need to keep moving to push the water through. This is required to feed but it also applies to the extraction of oxygen from water as it passes through their gills and if basking sharks stop moving, they will asphyxiate and die.

Wildlife tours

Way back in 2007 I was lucky enough to swim alongside the world’s largest fish in Western Australia, the whale shark. It is a bit of a pity therefore that I have not managed to get even a glimpse of the world’s second largest shark yet, our very own basking shark.

This year I am determined to tick these magnificent creatures off my bucket list and despite owning a kayak, I think I will prefer to rely on the skills and local knowledge of one of our fabulous marine wildlife tour operators. It is also always worthwhile to keep an eye out from land and all the better if you have binoculars.

Even if you aren’t lucky enough to spot basking sharks you have great odds of seeing seals, dolphins, porpoises or maybe even a whale. We are really very lucky to have the opportunity to see such amazing marine creatures without having to travel half way across the world.

• Ann Haigh MVB MSc MRCVS is a Skibbereen resident, a mum-of-two and a veterinarian with a masters in wildlife health and conservation and she is passionate about biodiversity and nature.