A new book co-edited by Fiona Murray looks more closely at the men and women of the Treaty delegation in 1921. She has also discovered that West Cork was well represented on the team

IN October 1921, a delegation of men and women, nominated by Dáil Éireann, left Dublin to travel to London.

Their mission: to meet the representatives of Great Britain and try to negotiate a peace treaty which would put an end to centuries of conflict in Ireland.

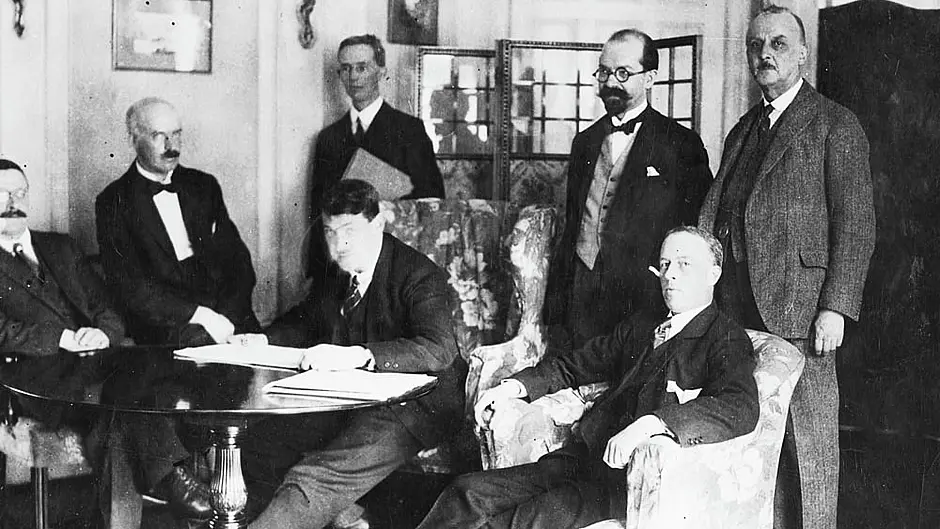

Apart from the five plenipotentiaries nominated by the cabinet in Dublin, the group also included a number of other key people: secretaries, advisors, stenographers, chaperones, and bodyguards. Aided by security and domestic staff, and by couriers who would carry messages between the two capital cities, this group would work tirelessly in the background in London, advising and supporting the negotiators.

Three months later, at 2.20 am on December 8th, the Articles of Agreement were signed in 10 Downing Street.

Who were these courageous men and women who quietly, behind the scenes, worked as a team in the public interest to try to create an independent and viable state?

Some 100 years after the event, the names of most have been forgotten, with even many family members unaware of the role they played.

But early in 2021, spurred on by the discovery in a family home near Dunmanway of boxes of documents belonging to my grandfather Diarmaid Fawsitt, one of the advisors, a small group of descendants of delegation members set about identifying the people involved.

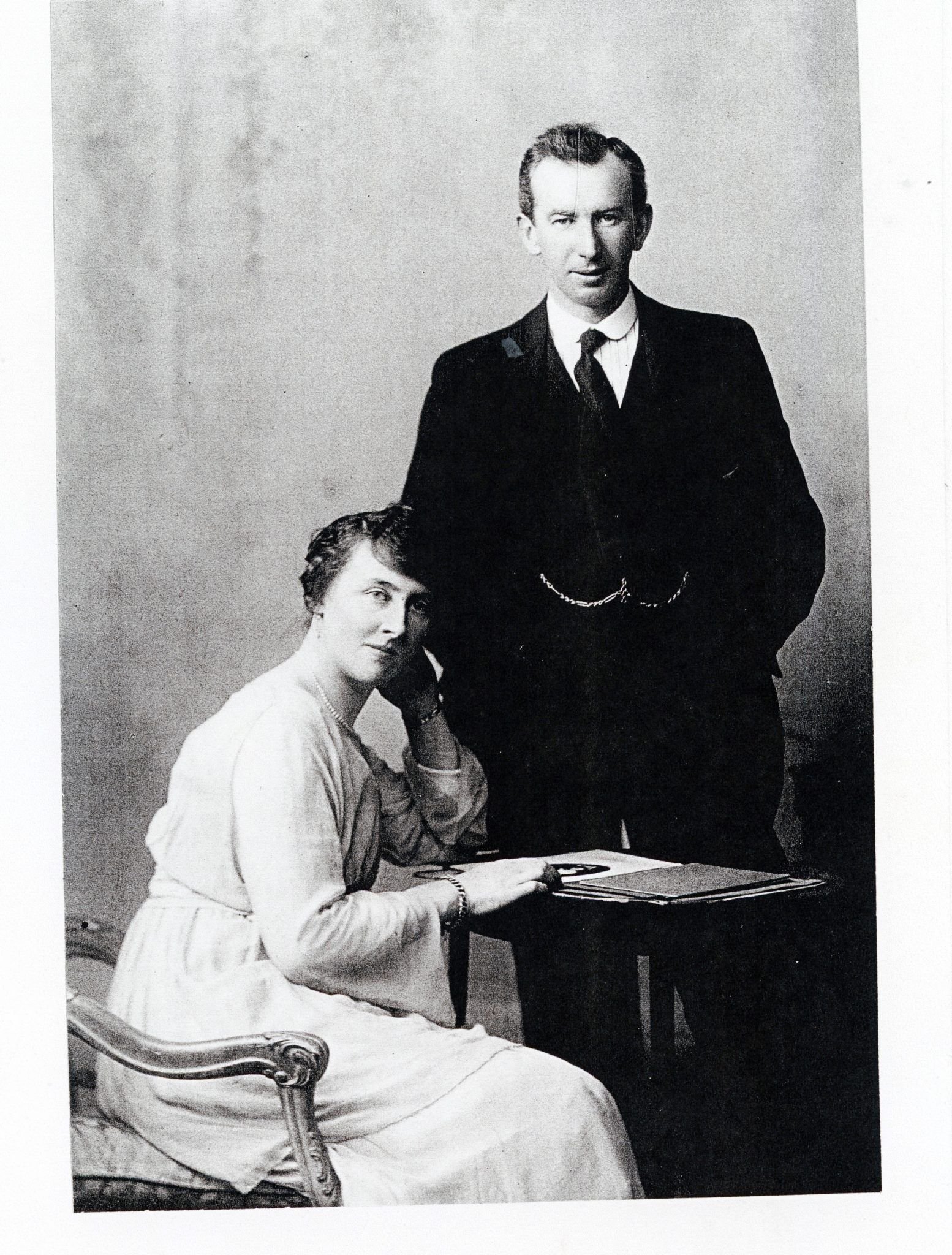

Kerryman Fionán Lynch, one of the four male secretaries, and his wife Bridget Lynch, née Slattery, who was appointed as one of the two chaperones

Kerryman Fionán Lynch, one of the four male secretaries, and his wife Bridget Lynch, née Slattery, who was appointed as one of the two chaperones

Over the course of a few months, by painstaking trawls through archives and histories of the period, as well as through genealogical websites, census and military records, obituaries, and death notices, the names of over 70 people were identified.

They were a diverse group: some belonged to the wealthier classes (landed gentry, baronets); others came from a professional background; and still others were from farming, shopkeeping, and artisan families. The only women were the five clerical assistants, the two delegation wives who acted as chaperones, and a few of the household staff and couriers. Of the seven delegation members born in Co Cork, four had West Cork heritage: Michael Collins was born outside Clonakilty; Diarmuid O’Hegarty (cabinet secretary) was from Skibbereen; Joseph Brennan (financial advisor) was from Bandon, and Diarmaid Fawsitt (economic adviser), born in Cork city, came from a Bandon family.

The group varied in age also. The youngest were still teenagers: 15-year-old Maureen Woods, who accompanied her mother on several journeys between Dublin and London, carried dispatches in the fur collar of her coat; while 17-year-old Seán MacBride, already an able guerrilla fighter, was personally recruited by Collins to help arrange a quick getaway if the Truce broke down.

Even Collins’ four bodyguards, as well as some of those who acted as security guards around the two large houses rented by the delegation in Knightsbridge, were mostly only in their early twenties. The oldest male member of the delegation, at age 59, was the barrister John Chartres, one of the four male secretaries.

The oldest female was Mary Folkard from Oldcastle, in Co Meath, who had been recruited as cook. Journalists in both Britain and the USA were fascinated by her, and eagerly sought her views on cooking potatoes and Irish stew.

‘[The Irish delegation] may be too busy to think about what they’re going to eat,’ she said, ‘but they’re not too busy to know if their food is well cooked. They’d die on English cooking. For instance, how the English cooks mistreat Irish potatoes. They peel them, but we Irish always cook them in their jackets.’

One journalist even implied that Mary was the secret weapon of the delegation, writing that ‘it’s said in Downing Street that it’s her seasoning puts so much pep in the Irish delegates’.

She helped provide a ‘home from home’ for the delegation, and even organised a céilí in the kitchen for the servants (who were from Irish or London Irish backgrounds) at Hallowe’en.

Following the identification of the 70 people involved, as many families of descendants as possible were contacted and asked to provide material for a commemorative volume.

All were most helpful, providing short biographies, personal or family memories, and photos for myself and Eda Sagarra (both of us granddaughters of two advisors) to use.

Our resulting lavishly illustrated book, The Men and Women of the Anglo-Irish Treaty Delegations 1921 focuses, not on the politics of that historic encounter, but on the people themselves and reveals some of the human stories behind the negotiations.

• The Men and Women of the Anglo-Irish Treaty Delegations 1921 is edited by Fiona Murray and Eda Sagarra and published by Laurelmount Press. It is available from www.buythebook.ie/1921treatydelegations (€16.95 plus postage) and copies are also available in some bookshops, including Bookstór in Kinsale.