Niamh O'Sullivan, curator of Coming Home: Art and the Great Hunger examines how art can help us remember the Famine

Niamh O’Sullivan, curator of Coming Home: Art and the Great Hunger examines how art can help us remember the Famine

OVER a million died during the Great Hunger, and from 1845 to the end of the century over three million emigrated. The Famine caused the disappearance of almost half of the population of Ireland. The impossibility of giving those dispossessed of life and home back their voices, the paucity of material traces, and the scarcity of contemporary images make it important to find other ways to remember.

Appalling conditions were the breeding ground for the single greatest loss of life in Europe between the Napoleonic Wars and the First World War – an outcome of systematic neglect by government. The Times blamed the victims: ‘a wretched, indolent, half-starved tribe of savages …’ (January 4, 1847). The Famine occasioned some of most searing accounts of living conditions, but its visual history is more complicated.

There are a small number of paintings contemporaneous with the Famine, notably the Cork artist, Daniel Macdonald’s ‘Irish Peasant Family Discovering the Blight of Their Store’ (1847). If famine presented difficulties for representation, and as no known photographs exist, it was largely through the mass-produced, illustrated newspapers that people learnt of events in Ireland.

A British illustrator visited a home scarcely exceeding the length of its occupier who had a wife and three children, concluding ‘he will have almost as much space when laid in his grave.’ The eight-feet square cabin was pitch dark, ‘the thatch was rotting: the cesspool up to the threshold of the doorway …’ There are very few images to match such descriptions.

Historically, violence or distress in art was softened for the sensibilities of the rich – distanced in time, and cloaked in mythology or allegory. Artists painted for those who simply would not countenance the purchase of pictures of rotting potatoes, emaciated bodies or diseased corpses to hang in their homes.

Illustrator

The Cork artist, James Mahony became the Famine illustrator for the Illustrated London News. In January1847, he toured West Cork, where he encountered a funeral every few hundred yards. The death toll was such that corpses were disposed of without wake or prayer. ‘I fear we must bury the dead coffinless in future. My God! What a revolting idea! Without food when alive, without a coffin when dead.’

One illustration, ‘Funeral at Skibbereen’ (ILN January 30th, 1847) had such a macabre impact that it was republished in the New York Herald a few weeks later. The stunted creatures look bewildered, the man atop the cart, brandishing his whip, deranged, the horse half dead, the land barren. The bodies, already eleven days dead, are about to be dumped in trenches, and covered with quicklime.

Mahony was appalled at the routinisation of death: ‘I saw (a man) with four coffins in a car, driving to the churchyard, sitting upon one of the said coffins, and smoking with much apparent enjoyment.’

The story of a family struggling to a graveyard and entombing themselves in a shed ‘surrounded by a rampart of human bones’ was beyond his visual powers. ‘In this horrible den, in the midst of a mass of human putrefaction, six individuals, males and females, labouring under most malignant fever, were huddled together, as closely as were the dead in the graves around.

‘So intolerable was the effluvium,’ he recoiled; ‘neither pen nor pencil ever could portray the misery and horror,’ he concluded (ILN, February 1847).

Divine will

The blight culled the people and cleared the land, and was welcomed as an instrument of divine will; Charles Trevelyan, chief administrator of famine relief, educed: ‘God sent the calamity to teach the Irish a lesson… The real evil with which we have to contend is not the physical evil of the Famine, but the moral evil of the selfish, perverse and turbulent character of the people.’

So if not illustrative, what can art tell us? Mahony’s Consecration of the Roman Catholic Church of St Mary’s, Pope’s Quay, Cork (c 1841) shows the determination of the Catholic Church to establish its authority within a disoriented culture. Jack B. Yeats’s Derrynane invokes Daniel O’Connell, as politician and landlord.

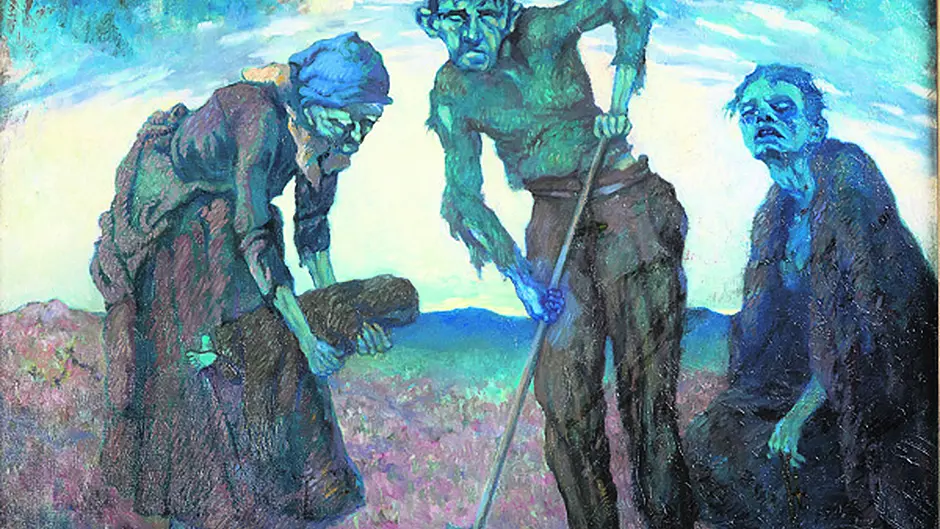

Lilian Lucy Davidson’s Gorta (1946) is the starkest imaginable evocation of death. In Micheal Farrell’s Black ’47 (1997-98) a raking light shows Charles Trevelyan in the dock before a jury of the dead, arraigned for his mismanagement of the Famine.

Reds, blacks, and browns are splayed on the canvas in Brian Maguire’s The World Is Full of Murder (1985), bodies piled on each other, as in mass graves. Equally William Crozier and Robert Ballagh engage with underlying themes of injustice and abuse of power – themes that resonate today.

Modernism, and the catastrophe of the First World War threw representation itself into crisis, leading to abstraction, expressionism and other formal strategies to deal with the pressures of reality. In this exhibition, the work of Hughie O’Donoghue, Alanna O’Kelly and Dorothy Cross suggests that it is through obliquity that disturbing experiences are rendered intelligible, enabling us to go below the surface, to find new ways of recovering the past.

• Coming Home: Art and the Great Hunger from Ireland’s Great Hunger Museum at Quinnipiac University opens in Uilinn, the West Cork Art Centre, Skibbereen on July 20th.

ARCHON IS ON LEAVE