In the first in a series of articles, political correspondent Harry McGee wonders if Fianna Fáil has learned anything from last year’s election

I know it’s simple and fatuous to compare sports and politics. But in my experience there are few other areas of life that give you better examples for explaining politics in clear terms, especially when it comes to the concepts of success and failure. In sport, when things go downhill, it quickly becomes stark and glaring and exposed. You are a winner or you are a loser. It’s black and white, with no hiding places, no room for compromises, or consolations.

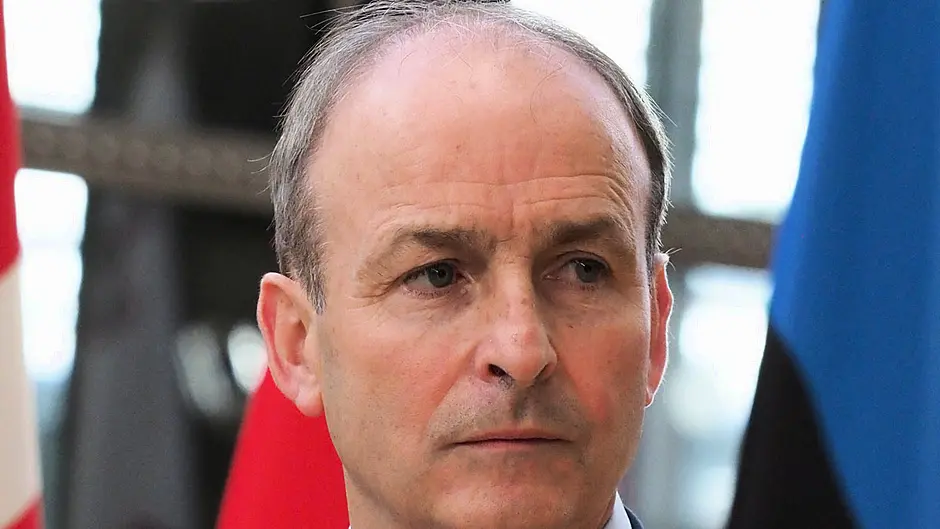

Micheál Martin reminds me of a certain type of football manager. They tend to be helicoptered into a club that’s failing, that’s fallen into the relegation zone or is languishing in a lower division. The new manager comes in, injects new energy into the club, brings in new ideas, a few new players, works a bit of magic. Within weeks the have-nots have become the haves, and are out of danger, or challenging for promotion. What Mick McCarthy is doing with Cardiff at the moment would be a good example of that.

The problem is: what do you do with Lazarus after you’ve brought him back to life? In the following season, those managers are expected to kick on and bring home trophies. With initial success comes unrealistic expectations. And more often than not they are not realised. Managers learn very quickly that miracles have a limited shelf life, and so do managers who fail to repeat miracles.

When Martin became leader of Fianna Fáil in advance of the 2011 general election, the party was in free-fall and facing annihilation. All of the 20 TDs who were returned were male and some were what you might call confirmed backbenchers, more focused on constituency minutiae than the national picture. The new leader’s reputation had also been singed by the crash. He was described as the first Fianna Fáil leader who might never be Taoiseach.

Martin’s first five years as Fianna Fáil leader were a success by any yardstick. He took a jaded beaten team and breathed life back into it. There was a harking back to the party’s formation in 1926 in the Le Scala Theatre and its famous Corú (or guiding principles). While the majority of the parliamentary party (and its membership) was morally and socially conservative, he ditched his natural caution by taking strong liberal stances on same-sex marriage and abortion referendums. In 2016, Fianna Fáil confounded expectations by winning 44 seats and running Fine Gael to six seats (an impressive performance given it was Fianna Fáil who had driven the State into rack and ruin, and it was Fine Gael and Labour which had banished the Troika and restored sovereignty).

That’s when the palsy set in. The oxygen that had got Fianna Fáil half way up the mountain needed to be replenished but the tanks were empty. It wasn’t all its fault. The circumstances were difficult. No party or traditional coalition arrangement was within an ass’s roar of a majority. Fianna Fáil entered into a confidence and supply agreement with Fine Gael. It was a gamble but it might have worked. The party supported budgets and votes of confidence in the Fine Gael-led government. They coalesced (as they always had) when it came to what they perceived as the national interest (such as the Apple tax case). It could have provided a path for future arrangements - a kind of half-way house for the non-Government party where it could still oppose and retain its identity.

Was it a fatal mis-step for Fianna Fáil for Martin to agree to that arrangement? Or did the mistake come with the leader’s decision (and it was his decision alone) to extend the agreement into a fourth year? The party’s grass-roots hated confidence and supply from the start and felt it would do the party no good. Martin now concedes it was a mistake to extend the agreement and he must shoulder the blame for that. He cited the importance of Brexit but, as we saw in Britain with Boris Johnson, elections would not have been an impediment.

The party did relatively well in the local and European elections in 2019 (but not ALL that well) and that buoyed it into a false sense of confidence.

There were two other strategic blunders it made going into the 2020 election. In his first term as leader, Martin often had to take the initiative. But to consolidate after 2016, he had to build up a strong leadership team. He did not do that, with most things focused around him. Secondly, whatever about returning to its 1926 roots, the party did a poor job coming out of confidence and supply in telling the public what it stood for and what made it different than Fine Gael.

In short the public wanted change and Fianna Fáil singularly failed to convince that public it represented change. The outcome of the election turned on the campaign. And it was Mary Lou McDonald who grabbed the initiative, on the disastrous RIC commemoration, on pension age, on being excluded from the RTE leaders debate. In the Virgin Media debate she did not stand on ceremony and wiped the floor with Micheál Martin. Fine Gael realised the changed direction of the wind and ran an unashamedly scare campaign against Sinn Féin. Fianna Fáil just did not seem to recognise the scale of the danger.

Over a year after that poor election, the party has still to complete its own inquiry into what went wrong. And you wonder has the party learned any lessons from its mis-steps. Is the grand-coalition with Fine Gael and the Greens going to be a repeat of confidence and supply (and not in a good way)? Why did he dismiss a coalition with Sinn Féin so vehemently?

When you speak to the TDs they say it’s all still about Micheál Martin. The party lacks a leadership team like there is in Fine Gael. ‘We have no deputy leader,’ says one. ‘Who is our Simon Coveney who can speak in a leadership capacity?’

Martin’s first seven months as taoiseach have been rocky. Again circumstances have made it very difficult. The first two months of his Government was a disaster with Golfgate and two Ministers resigning. Covid-19 has been all-consuming and the media and opposition are merciless if a perfect solution is not found for every facet of a fiendishly complex problem. At this moment in time nothing else matters. The Government has bet the house on vaccines. If that works, it will survive and can then focus on other things.

Martin really needs to work on his, and his party’s, limitations and shortcomings. At the moment the five Ministers seem isolated in their silos. He needs to appoint a deputy leader who can stand in for Leaders’ Questions regularly. He needs to sit down and figure out what he stands for as taoiseach and then articulate it. He is doing too many interviews at the moment – if you are doing that you can’t avoid blather and platitudes. There’s a lot to be said for having a simple robust message and sticking to it.

He’s managed to make some headway with the shared island idea. But even that initiative is problematic.

He seems to have changed Fianna Fáil policy on a united Ireland without consultation with his own colleagues. His vision of a shared island is very inchoate at this moment of time - listening to diverse voices is all very well but it needs to be distilled into a position that is nailed-on.

Napoleon banged on about unlucky generals but Martin is more a general in unlucky times.

He and Fianna Fáil badly need the rub of the green. There are few who see him lasting as Fianna Fáil leader beyond 2022. Essentially he has 22 months in which to leave a lasting legacy.

• Harry McGee is political

correspondent with The Irish Times and on Twitter @harrymcgee