Beware of translating those West Cork placenames, author Jerome Lordan told a lecture on the subject, held online recently, because you can be easily led astray without the full knowledge of what they mean!

FARMERS and fishermen are often the only people who retain some of the old names of places in our region, said historian Jerome Lordon at a recent talk on West Cork placenames.

The talk was part of a series of online lectures for members of Duchas Clonakilty Heritage committee.

Jerome said that non-administrative names are used only by people in their own locality, and are referred to as ‘minor’ placenames.

Addressing the audience, Jerome quoted broadcaster and writer Manchán Magan when he said that minor placenames are the ‘lost language of landscape’.

These are not the names of provinces, counties, baronies, parishes or townlands, but old names that have been, in many cases, long forgotten, but often tell the ‘greater story’ for that area.

He used Dursey island as a great example of where the placenames still exist because of their isolation from the mainland and lack of influences that may have otherwise led to their demise.

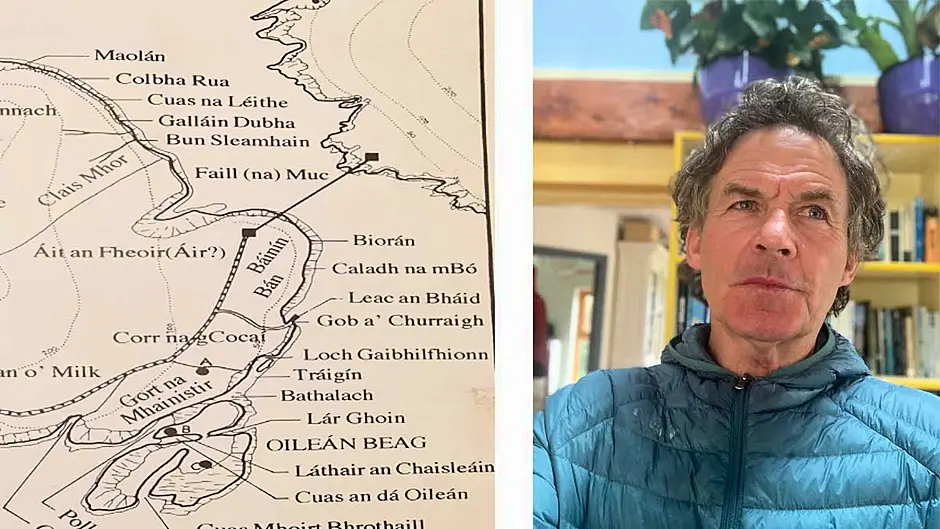

He referenced the book Discover Dursey by Penelope Durell and the accompanying map gives details of the many placenames on the island.

The bull rock, for example, was known as Tigh Doinn – it was thought that the soul went through the gap in the bull and into the next world. There is another placename near the part of the island where the cable car arrives. It is called Ait an Fheoir – place of fear – referencing the slaughter of the entire population of Dursey in 1602 by George Carew and his forces. It is believed they were run off the cliff into the sea at that point.

Another one is Caladh na mBó – the landing place of the cows, which can also mean a ferry, but it makes one wonder, said Jerome, did they swim the cattle across Dursey Sound, or transport them in boats in olden times?

Jerome, who himself has undertaken some research into the placenames around the Old Head of Kinsale, also referred to the great work of Dr Eamon Lankford who was aided by up to 200 researchers to carry out a survey of the placenames of Cork and Kerry. He also referred to the Meitheal Logainm website, which allows users to read and add place names in their own localities.

Jerome said that a lot of placenames were handed down orally from generations and this may have led to a lot of guesswork with spelling. This is especially the case when the generations of Irish speakers began to die out.

Animal names are often used for placenames, too, he pointed out, and very often it was because of the shape of the topography.

He also gave the example of a place at the Old Head called Cistin (meaning kitchen in English), which may have been because it was a sheltered spot where a fisherman could go to prepare food or get a night’s sleep. But on the ordnance survey map, it appears some distance from that point, and is renamed as ‘Kitchen Point’. Jerome said this gives a good example of how names can be transposed, often incorrectly, into modern day maps.

There are also quite a lot of Norse names in the region, like Dursey and Fastnet. And Osthaven for ‘Oysterhaven’. But the further west you go, the less there are.

He said that agriculture also has a big role to play in the naming of fields which were often called after the family that owned them.

He also pointed out that sometimes literal translations can be incorrect – for example ‘Capall’ does not mean ‘horse’ in many instances. It actually means a small, sunken rock.

And often the use of madra in coastal placenames does not always mean dog – it can actually mean ‘sea-dog’ – which is an otter! And he added a word of warning when trying to understand some placenames: ‘The only reason they anglicised Irish names was to make them easier for English speakers, but often they made them gobbledeegook! It’s a hybrid name and it’s nigh on impossible to decide what it means, unless they have the original form.’