An Irish Film Institute programme is preserving films shot in the south west dating as far back as a century and aims to foster a relationship between the community and its history, writes Dylan Mangan

Patrick Carey’s film is an exploration of the wild desolation of West Cork, featuring the unique flora and fauna of the Beara peninsula.

Patrick Carey’s film is an exploration of the wild desolation of West Cork, featuring the unique flora and fauna of the Beara peninsula.

WEST Cork has always looked good on camera. It’s a fact that has drawn a number of big studios to the region, with Netflix and ITV both sending large budget productions here in recent years.

While the Obama-produced Bodkin and Graham Norton’s Holding garnered a lot of attention, a number of smaller, more local films have been produced in West Cork over the past century as well.

At May’s Fastnet Film Festival in Schull, several films shot in West Cork by both professional and amateur filmmakers from the 1920s to the 1970s were shown in a special screening organised by the Irish Film Institute (IFI), with many available to view online.

Part of the IFI’s Local Films for Local People programme, their ‘West Cork on Camera’ event, delved into the vaults of the IFI Irish Film Archive to show archival gems made in West Cork and the surrounding area.

This year’s selection included Paddy Carey’s Beara (1979), the rarely-seen King of Spades (Monard, 1947) and Father Jack Delany’s West Cork (1930s), along with footage of Michael Collins and more.

The programme aims to foster a positive relationship between a community and its history, through the use of films created in those communities.

‘The idea was that we would be a bit strategic in curating programmes that were county-specific, that we could bring around the country,’ said Sunniva O’Flynn, head of Irish programming at the IFI, who tailored the festival programme to a West Cork audience.

‘Before this programme, we were reacting to requests coming in – you might find that you’d have requests coming in from the same county each year – and there were counties that were overlooked. And yet we knew that there was valuable material there that deserved to be seen by communities who would probably have a more informed engagement with the films than other audiences would.’

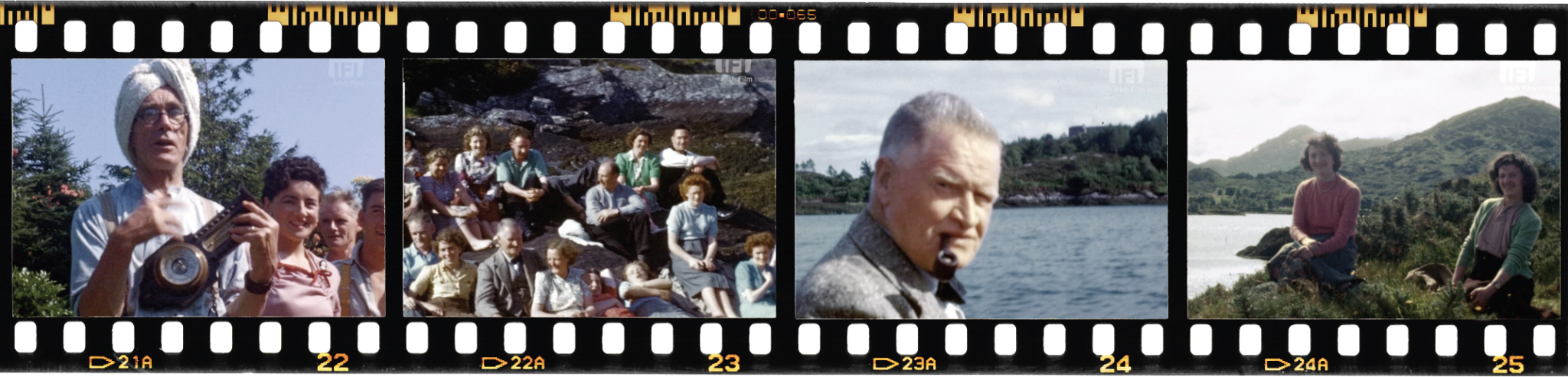

Fr Jack Delany’s short film shows a visit to Glengarriff and West Cork in the 1940s; The holidaymakers (friends of Fr Delany) relax in the garden of Casey’s Hotel, take a boat trip, bathe in the sea and join in an impromptu group singalong and a spur-of-the-moment dance.

Fr Jack Delany’s short film shows a visit to Glengarriff and West Cork in the 1940s; The holidaymakers (friends of Fr Delany) relax in the garden of Casey’s Hotel, take a boat trip, bathe in the sea and join in an impromptu group singalong and a spur-of-the-moment dance.

Each programme is designed to include a mix of films, with both fiction and non-fiction, silent films and ‘talkies’ all part of the brief, along with landscape and more social pieces as well.

‘Our agenda in some respects is to introduce audiences to the breadth of material that has been made in Ireland,’ said Ms O’Flynn, on the importance of variety. ‘That would include a good deal of amateur material, because professional production didn’t really take off with any kind of consistency until the mid-80s.

‘On the one hand, they might have been commercially-produced material, serving the agenda of a local business, or they might have been amateur productions. But in these programmes that we present, we would try to include a variety of forms of film.

‘As you can imagine, there are some counties that would have a good deal of material, and we can pick and choose. There are other counties where film crews arrive less often, so we’d have less of an opportunity to show different kinds of film.’

The preservation of archival footage is an important part of Irish social history, according to Ms O’Flynn, which can be painstaking work at times, but is greatly rewarded by audience reactions. In Schull this year, the audience were transported back in time to Beara in the 1970s and shown how West Cork was advertised as ‘the Irish Riviera’ for British holidaymakers in the 1930s.

‘And 99% of the time, there’s a great warmth in the response to the material,’ said Ms O’Flynn.

‘Personally, I’m conscious that people are grateful that the material is being preserved, you know, because otherwise, it might languish in people’s attics or be thrown out.

‘People might get them transferred to another format and then dump the original films, which is horrendous. But, when films come into us, when they’re preserved and they’re minded, people appreciate that. But they also then do appreciate the experience of being in a room with others, that shared response to the material, the shared sense of ownership of the past and of memory, that business of recognising things and the muttering when people say, oh, you know, that may be the school I went to or, you know, they might recognise a landscape. And that’s a very satisfying, pleasurable experience for audience members.

‘There would be more material, certainly, from West Cork that we haven’t yet screened, but it may be silent amateur film, and that can present challenges for contemporary audiences,’ she added.

‘We have often presented that work with live music, which is quite lovely and creates a whole different kind of event.

‘But there may be times that we don’t have an opportunity to do that, or where the material doesn’t lend itself to that kind of presentation.

‘Because the fact is, with a lot of home movies, so to speak – films made by amateurs for consumption by their families – there would have been an audible response to it, like the muttering of the family identifying themselves. Like, you know, “That’s my communion”, “Why did you make me wear that frock?”.

‘And so it’s quite a different undertaking to show the material to audiences who might not have that immediate family response. There’s all sorts of issues at stake here that would influence what ends up in a programme.’

For the IFI, archival work continues on an ongoing basis, with collections that span from 1897 to the present day from all parts of the country.To specifically view Michael Collins footage on the IFI archive, search ‘Michael Collins’ on ifiarchiveplayer.ie

The IFI Player

Films mentioned in this article are available on ifiarchiveplayer.ie. To watch, search for the film’s name on the website and click on the corresponding result.

The IFI archives have hours of footage from Irish history across the island, so you can also search for terms like ‘Cork’ or ‘Michael Collins’ and see what material is available to watch on the player.

Films in the West Cork on Camera programme available to watch online

Irish Tourist Association: Irish Riviera – www.ifiarchiveplayer.ie/travelogues-the-irish-riviera

Father Jack Delany: West Cork – www.ifiarchiveplayer.ie/father-delany-collection-west-cork

Patrick Carey: Beara – www.ifiarchiveplayer.ie/beara/