This week marks the anniversary of James Joyce’s death in Switzerland in 1941. But how many people realise that the Skibbereen Eagle’s earlier censuring of the Russian Tzar may have inspired passages of Ulysses, as Joycean scholar Brendan Kilty has discovered?

EXACTLY 125 years ago this year, in September 1898, The Skibbereen Eagle instilled fear into the Russian Tsar, a butterfly effect not replicated until the West Cork fishermen saw off the Russian navy last year.

The eye of The Skibbereen Eagle focused on the Tsar’s success in securing an ice-free warm-water base for the Russian Navy on China’s Yellow Sea.

But only two weeks earlier, in something akin to modern day political sports-washing, Tsar Nicolas II sent an unexpected invitation to every government accredited to his Imperial Court.

The Tsar’s rescript invited these governments to a conference ‘to occupy themselves with the grave problem of excessive armaments.’

In truth it disclosed his military vulnerability dressed up as his pursuit of world peace.

The Tsar told the world that he was keen to ensure to all people ‘the benefits of a real and durable peace, and above all of putting an end to the progressive development of the present armaments.’

With his Chinese warm water naval port now secured, Tsar Nicholas II set out to achieve this worthy ambition ‘by means of international discussion’ at his peace conference.

And it met with great success, for within only a few months the Tsar’s peace conference created the Permanent Court of Arbitration where the arbitration and peaceable resolution of (some) disputes between nations continues down to this day.

The peace conference also developed ‘Rules of War’ for the treatment of prisoners of war. It even banned, for the next five years at least, the discharge of projectiles and deleterious gases from balloons.

Under Bismarck, the plethora of small German states had coalesced as the increasingly powerful German Empire, with the dynamo of its Prussian siege engine massed on its border with Russia.

Acutely conscious that his guns could never match those of his neighbour, Tsar Nicholas II set out to prioritise peace over his inevitable defeat.

Andrew Carnegie, the philanthropist who built 80 libraries across Ireland also funded the construction of the Tsar’s dream home for the Permanent Court of Arbitration at the Peace Palace in The Hague, Netherlands.

The list of signatories to this Peace Convention today reads as an eerie who’s who of hubris and history – powerful people whose memory is neither remembered nor honoured.

It included the Prince of Montenegro and the Prince of Bulgaria and the long-forgotten Kings of Bohemia, Hungary, the Hellenes, Italy, Portugal, Serbia and Siam.

Imperial majesties, such as the Shah of Persia and Her Majesty the Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, Empress of India also signed, as did the Emperors of Germany, Austria, China and the Ottomans.

Of course, the ‘Emperor of all the Russias’ also signed up.

In the same month as the Tsar’s call to action in 1898, the son of a Corkman – claiming a connection to Daniel O’Connell – enrolled at Cardinal Newman’s University on St Stephen’s Green in Dublin from where he graduated in 1902. While it seems to scholars that young James Joyce was possessed of a stunning awareness and broad knowledge, much of his texts are derived from or informed by the newspapers of his time.

For the impecunious Joyce, local, national and international newspapers were readily and freely available to read in public libraries.

Today, these same public libraries act as ‘warm banks’ – places to visit to stay warm in the face of impossible domestic energy bills caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

But Joyce was not the only one reading English language newspapers.

They were being read in Moscow and St Petersburg as well.

We know this from the Tsar’s father, Nicholas I, who boasted during the Crimean War (1853-1856) that he had no need of spies.

He was learning everything he needed to know by reading Dubliner William Howard Russell’s account of the Crimean War published by the Times of London and read by embassies everywhere.

Joyce was nothing if not up-to-date when he weaved the Tsar’s Rescript and notions of world peace and international arbitration into Stephen Dedalus’ conversations with his fellow students at Newman House on St Stephen’s Green where they gathered around the Tsar’s portrait collecting signatures.

They were preparing to send the Tsar a testimonial of gratitude for his pursuit of world peace and the arbitration of disputes among nations.

They had every reason to believe that a Tsar name-checked by The Skibbereen Eagle would read the praise of their Testimonial.

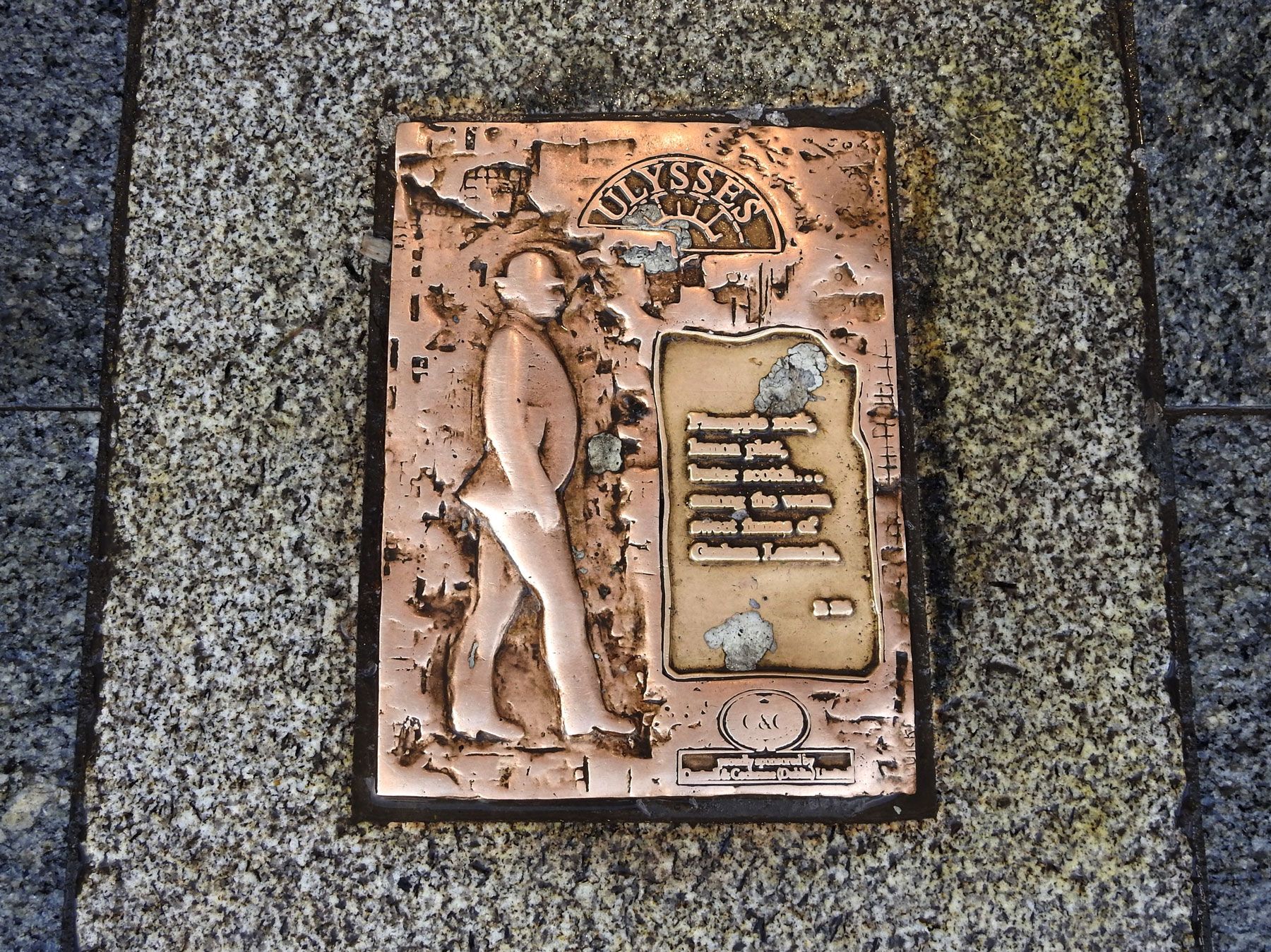

Joyce was clearly impacted by the Tsar’s Rescript and The Skibbereen Eagle as he threads the debate about world peace and international arbitration from Stephen Hero, begun in 1903 just after his graduation, to Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man published before World War I and again, after the horrors of that war, to Ulysses, published in 1922.

Clearly, the watchful eye of The Skibbereen Eagle had spawned an imitator in Joyce and a reader in the Tsar.

Perhaps, it is time now for The Skibbereen Eagle to re-send its impactful historic note to the current Tsar.

National and international papers, please copy!

Joycean Brendan Kilty, above, has examined the links between Joyce’s Ulysses and the Skibbereen Eagle’s references to Tsar Nicholas II.

Joycean Brendan Kilty, above, has examined the links between Joyce’s Ulysses and the Skibbereen Eagle’s references to Tsar Nicholas II.• Brendan Kilty SC is a senior counsel, arbitrator and Joycean.

His human rights book ‘101 Reasons Not to Execute Someone’ is due to be released in 2023.