Following the passing of former Southern Star reporter Paddy McGarvey, his family reached out and reminded current reporter Jackie Keogh of the gifted writer’s memoir and its colourful recollections of his first impressions of Macroom

PADDY McGarvey – who worked for The Southern Star as a young reporter in 1946 – has died in England, aged 95.

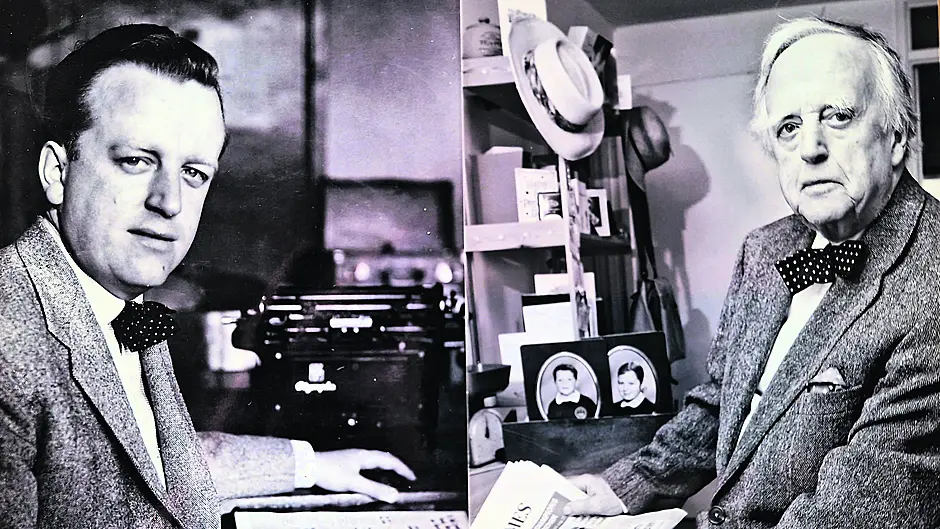

Paddy’s son Feargus informed us of his dad’s passing and shared with us a pair of photographs spanning 50 years.

‘Paddy was very pleased to be wearing the same jacket and bow tie in both,’ he said.

Feargus also sent excerpts from My Ireland, My England, the book his father wrote.

In it, Paddy describes his first meeting with his editor, Joseph O’Regan, and his arrival in Macroom. Reading those pages was like the proverbial window to another world.

‘My destination,’ Paddy wrote, ‘was Macroom, twenty-five miles west of Cork city, population 2,000, where I would commence a district news-gathering role for The Southern Star’s home newsroom in far off Skibbereen.

‘The paper’s new owner, Joseph O’Regan, a former creamery owner, met me at Cork rail terminus wheeling a bicycle.

‘We shook hands, and he said: “Here, you’ll need this where you are going,” handing me the bike.

‘For a moment,’ Paddy said, ‘I had the horrors he wanted me to cycle the 25 miles to Macroom.

Paddy’s alarm was momentary as the bike was bundled onto the roof of a bus and off he went to Macroom.

With dreams of being a famous columnist swirling in the 18-year-old’s head, Paddy experienced his ‘first gnawing doubts’ with the opening views of his destination.

‘The thatch on a long line of one-storey terraced houses hung over the pavements in tatters. The street looked and felt as if it had been ploughed, the bus thumping and banging its sump on the street’s unending saddle hump.

‘I was reminded of a famous photo of the Great War, a Flanders village through which a hostile army had passed.

‘Passengers lurching left and right and left again bumped their heads on the windows while gripping the seats in front for fear.

‘I would learn the cause later – it made some of my opening stories – but at that stage, I felt I had made a terrible mistake and could not wait for the bus to stop, jump off and arrange my journey home. Mr O’Regan’s bike could end up in Killarney for all I cared.

‘I had made up my mind, no deal, no way, not here, not my kind of town,’ Paddy wrote, but of course within minutes of stepping off the bus West Cork’s famous hospitality dispelled his unease.

‘A roly-poly little woman stepped forward from the shop door beaming from a wide smile and a welcoming outstretched hand.’

‘In retrospect,’ he wrote, ‘I have long since felt that the immature teenager who had lost his mother at six was at that moment caught up in this warm-voiced lady’s effusion of motherly care.

‘A man with a bristly moustache, her husband Denny, wheeled my bike through the shop and house to the back yard and I was home.’

The story rolls on. Paddy bought a motorbike but it needed a battery. Locals referred him to Bertie Smithers.

‘Bertie Smithers,’ Paddy thought, ‘that’s a strange name around here.’

The local gave him an eye-roll and said: ‘Ah well, you see, he was a Tan right enough but he married a grand girl and sure that was that.’

‘Not exactly what you read in histories,’ the young reporter from Armagh thought. ‘What a pity they did not afford such forgiving grace to the one of their own who founded modern Ireland.’ The author was, of course, referring to Michael Collins.

The book is rich in detail of his early days, reporting from the district court, conversations with contacts, and observations on the every day.

‘My Armagh accent grates on Cork ears with momentary smiles of surprise, followed by impeccable manners across the gaps of misunderstanding,’ he wrote. While Gerry T – a mint-fresh member of An Garda Síochána – appointed himself as translator, ‘an excuse to join the craic.’

This part of Paddy’s career comes with lots of life lessons and is a pure joy to read, like his late night encounter with a wild donkey on the back roads of Macroom.

‘Not for the first time was my motorcycling life saved by a spongy Irish ditch, leaving all bones intact. When I regained the road, and struggled to lift the heaviest bike then around, I discovered I had no lights.

‘Cautiously,’ he said, ‘I walked the bike to the edge of the village where a single lamp might illuminate what was wrong. What was wrong with the lamp was the thin cadaverous guard standing under it, notebook in hand, in which he proceeded to book me for no lights.

‘The boyo had seen me coming, his day in court at last,’ wrote Paddy, who went on to confess: ‘I was to leave Cork soon afterwards, and never did pay that fine.’

Paddy was to emigrate to England. Fleet Street had beckoned. It was in England that he married Pam and together they had seven children: Averill, his step-daughter, Shane, the late Conal, Fiona, Catherine, Niall and Feargus.

Paddy’s book was published in 2012 and readers of The Southern Star will be delighted to know that it is still available to buy online.