There are few greater joys in life than sitting with your family in the garden, watching your solar panels quietly earn their keep.

I installed mine last year, and the satisfaction is part smugness, part survivalist, but I find myself obsessively checking the app on sunny days.

‘We’re exporting to the grid! We’re in profit! Ye’re going to college, lads!’

Of course, five minutes later, the clouds drift in over Howth and I’m darting around the house turning off lights again.

But this last spell of this weather has seen them really shine, pun intended.

In the last few months, I’ve noticed lots more panels going up on our road and it’s typical of many Irish streets. Ireland’s solar capacity is growing, with installations rising daily. Thanks to advances in technology and some solid innovation on the part of our Chinese friends, solar panels cost significantly less in 2025, with typical installations paying for themselves in as little as six or seven years. The SEAI grants have been trimmed back slightly, but they’re still making a difference, and it would seem wise that the government leave some carrots out there to encourage more uptake in the years to come. But on the evidence of recent shenanigans, they might find some way of making a mess of it.

It’s all a performance

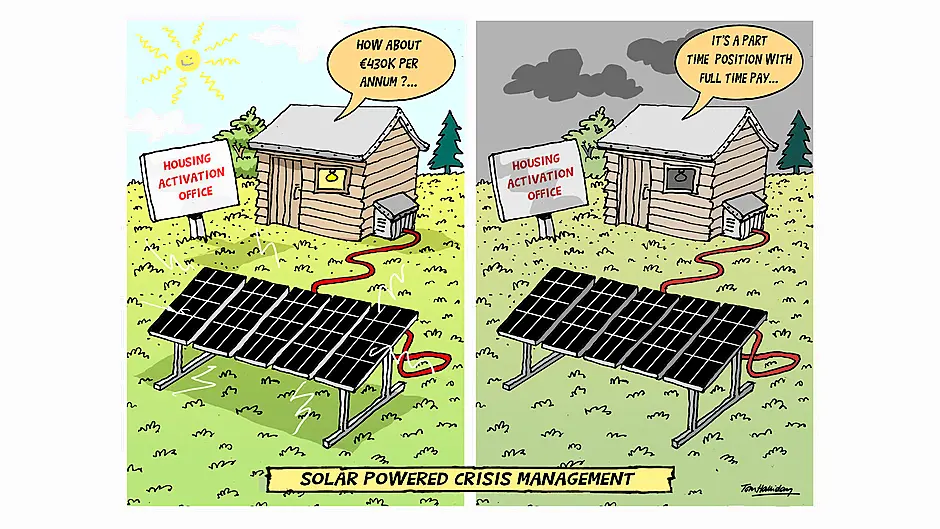

Last week, we witnessed another spectacular government own-goal when plans to appoint a housing ‘tsar’ collapsed. Brendan McDonagh, the NAMA chief executive who was the government’s preferred candidate, withdrew his name from consideration after Fine Gael blocked his appointment.

At a Cabinet committee meeting, Tánaiste Simon Harris complained that Fine Gael had been ‘kept out of the loop’ about McDonagh’s potential appointment. But what really set tongues wagging was the salary that McDonagh would have kept – a cool €430,000, almost twice what a cabinet minister earns. You could nearly graduate to oligarch level on that kind of bread.

Harris confirmed his opposition on Friday’s Late Late Show, saying plainly that he didn’t think such a salary was appropriate for someone overseeing housing reforms to help people who can’t afford homes. The whole saga has turned into a proper barney between Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael.

For the public, it was another chapter in the long-running saga of How Not To Solve A Crisis. Task forces, action plans, housing activation offices, tsars; we’ve had every performative solution but housing itself. Meanwhile, rents spiral, evictions rise, and the waiting lists stretch toward out into the never-never.

Housing is a crisis all over the western world. It’s a common problem across many countries. And it feels perplexing given we managed to produce it at scale in the past when times were a lot harder. A little personal anecdote, but I had my kitchen fitter in during the week and he met my parents. They observed how busy he must be, given how hard it has been for me to get him back in to finish the work. ‘There just don’t seem to be enough fellas like me out there to do the work that needs doing’, he said. And there it is: we all want houses built, but few of us are encouraging our kids to get a trade.

Titles for all the lads

The short reign of the would-be Housing Tsar raises an obvious question: if we’re going to start handing out ceremonial titles, why stop at housing? Ireland could appoint a whole pantheon of tsars. We could have a Broadband Tsar tasked with getting decent Wi-Fi to places that still think ‘buffering’ is a weather condition. We could have a Middle Lane Tsar to discourage drivers who camp out in the middle lane of motorways. Or even a Eurovision Tsar to deal with the next inevitable song contest-related scandal, whether it be Samantha Mumba’s emoji incident or, for instance, a witch from West Cork causing a geopolitical earthquake. We could even extend the scheme to sort out RTÉ’s financial woes - Dancing With The Tsars, anyone?

Theroux and The Settlers

Speaking of geopolitics, if you’re looking for something to properly re-engage your brain this week, Louis Theroux’s new BBC documentary on Israeli settlers is pretty much essential viewing. In The Settlers, Theroux allows ultra-nationalist Israeli settlers to speak with perfect openness, creating what the New Statesman called ‘a deathly warning.’ Fourteen years after his first visit to the West Bank, he returns to find the situation has dramatically worsened. The documentary has sparked predictable controversy, with The Jewish Chronicle asking, ‘Why is the BBC showing the worst Jews they could find?’, while The Guardian gave it five stars. What makes Theroux so effective is his calm, almost statue-like approach. He simply lets people talk, allowing their words to do the work.

In a world drowning in hot takes, Theroux offers something rarer: the power of patient observation and uncomfortable questions. It’s a reminder that sometimes the most revealing journalism isn’t about stating opinions, but about having the courage to let people fully reveal themselves.

What is revealed in The Settlers is truly, truly depressing and you get the sense that any hope of a peaceful settlement in that part of the world has long departed. There is instead a sense of inevitability about it all, that borders on terrifying.